The most historic moments are inextricably linked with the popular music of that time. This is most obvious when looking at the music that was created during the social and political turmoil of the 1960s. Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” plays in my head when I think about the civil rights movement. I can hear the unmistakable harmony of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young repeating “four dead in Ohio” when watching news reports of the May 4, 1970 Kent State shootings. The political messages in the music of the 1960s and 1970s are clear: These songs are either rallying cries against segregation in the American South or pleas for the United States government to end its involvement in the bloody, unpopular Vietnam War.

By the 1980s, American culture had changed dramatically. The disorder and tumult of the preceding decades gave way to the conservative leadership of Ronald Reagan. This shift in political regime brought with it a new economy that favored large corporations, like record companies. The Reagan Revolution was coupled with an evolution in satellite technology, creating a new national and worldwide media landscape. Niche networks like MTV were soon broadcasting this new medium of music videos 24 hours a day into middle-class homes across the United States and the Western world. New politics, new economics, and new technology came together at the same time. As a result, not only were musicians earning more cash, but the currency of celebrity was worth more than ever. With MTV, it was no longer about how you sounded, but how you looked. These factors impacted the causes that artists supported and the ways they tried to bring about change.

What were artists singing about in the 1980s? That’s one of the questions I ask in my new radio documentary, “Concerts of Change: The Soundtrack of Human Rights,” premiering on SiriusXM Volume Channel 106 on March 22 at 1:00 PM EST. In this six-part series, I argue that the period from the late 1970s to the early 1990s was an era in which artists’ efforts played an exceptional role in the universal struggle for human rights. Two of the greatest examples of artist humanitarianism in the 1980s focused on injustices occurring on the continent of Africa: Bob Geldof’s Ethiopian famine relief efforts and Steve Van Zandt’s Anti-Apartheid “Sun City” project. These campaigns, along with human rights organization Amnesty International’s use of musicians and concerts to raise its profile in the United States, should be understood together as examples of the era of human rights.

Let’s consider Bob Geldof. In October of 1984, Geldof was sitting down to dinner with his partner and six-month-old daughter. He looked up at the television and what he saw horrified him. The BBC’s Michael Buerk was reporting from Ethiopia. A famine was ripping through refugee camps as a result of the country’s then decade-long civil war. Inspired to help those suffering thousands of miles away, Geldof and Midge Ure (from the band Ultravox) wrote the song “Do They Know it’s Christmas?”. Geldof then brought together a cadre of the most popular artists of the day to form Band Aid. Most of the artists were British, but one band, U2, was from Geldof’s native Ireland. Geldof gave their singer the most powerful – if not controversial – line in the song: “Tonight thank God it’s them instead of you.”

The song was heard around the world, but it was the video featuring some of the biggest stars from MTV at the time that brought about something no one had ever seen before. Duran Duran, U2, Bananarama, Sting, Phil Collins, standing together on risers bellowing, “Feed the World.” ABC contributor Chris Connelly described it for me this way, “It was like seeing the sixth grade singing a Christmas carol.”

Geldof’s efforts in England inspired American artist Harry Belafonte and music manager Ken Kragen to marshal the support from artists Quincy Jones, Michael Jackson, and Lionel Richie. This team wrote and produced the song “We Are The World” for the USA For Africa project. Bob Dylan, Diana Ross, Willie Nelson, Cindy Lauper, and Bruce Springsteen are just a few of the 40-plus American popular music icons who sing on the recording.

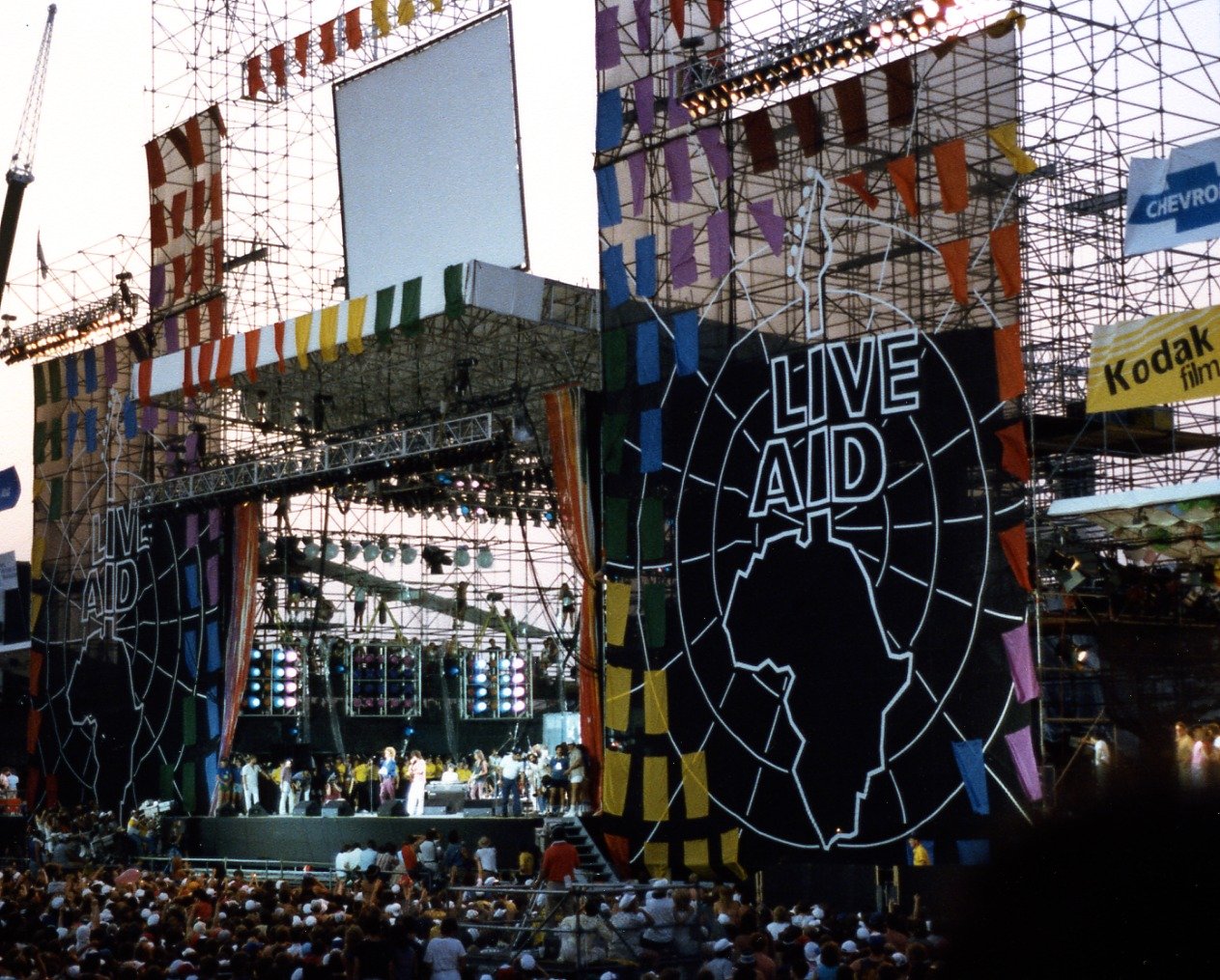

Band Aid and We Are The World joined together at the Live Aid concert on July 13, 1985. Live Aid was unprecedented. Two concerts were occurring simultaneously on two continents. 72,000 people in attendance at London’s Wembley Stadium, another 100,000 at JFK Stadium in Philadelphia. Perhaps most stunning when considered from the fragmented media landscape of 2022, is that Live Aid was watched by an estimated two billion people – 95 percent of the televisions in the world were tuned to Live Aid. A mere four-second delay in the satellite feed between London and Philadelphia pushed technology to its limits. It was a tangible example of globalization – the first viral moment.

Satellite technology in the 1980s brought more than Live Aid into our homes. It also brought us CNN. It gave us instantaneous images of famine and oppression from around the world. By the end of the decade, we watched in realtime as young East and West Germans used sledgehammers to bring down the Berlin Wall, signifying the end of the Cold War and the birth of a new, unknowable historical moment.

In the 1980s, technology also helped artists lead a unified coalition across age, economic background, and political identification on behalf of the struggle for human rights around the world. Forty years later, we are living with another new technology. A technology that encourages creators to flood our phones with more information than ever, faster than we can process it, leaving the media we choose to digest – and its verification – up to our own interpretation.

Except for the outrage and protests sparked by the viral video of the murder of George Floyd in May of 2020, today’s social media no longer serves the purpose of bringing us together. Rather, it is tearing our society apart by creating hermetically sealed echo chambers that pit average citizens against each other on almost every major issue. The question now is whether today’s artists can figure out how to harness a fragmented media landscape, pull each of us out of our independent information silos, and bring us together for a good cause.

Bob Crawford

Bob Crawford, is the Bassist for The Avett Brothers, Co-managing Partner for the Press On Fund, and Co-Host for the Road to Now podcast.