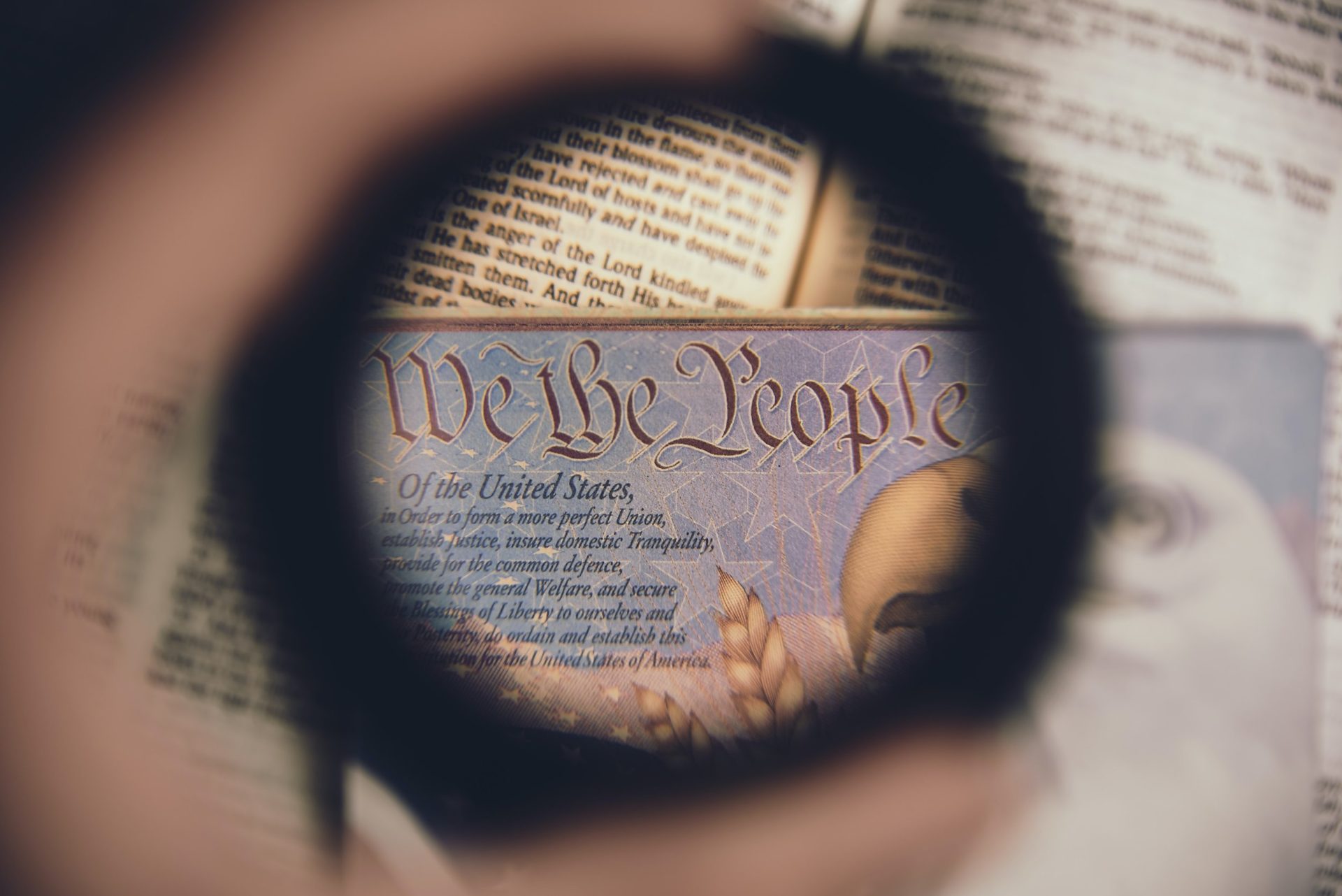

The Constitution of the United States lets us consider who we are today. It does not limit us to who we were centuries ago. This assertion is without regard to the outcome of any recent Supreme Court decision but focuses on matters that may be yet to come.

There has been a considerable amount of public dialogue this summer over “originalism,” which (broadly speaking) is the theory that the Constitution should be interpreted solely according to its original meaning. A trending and very strict concept of “originalism” has emerged in recent public discussions that would limit our fundamental rights to those recognized at periods in the deep past when the Constitution or certain key amendments were ratified. The supposed justification for taking this strict approach is that—without it—judges residing outside of the electoral processes could declare “new” rights that may be inconsistent with the will of the populace. Holding to a fixed past, therefore, protects against actions by unelected judges, or so the argument goes.

But democratic principles should press our courts to interpret fundamental rights with an eye toward today’s context, not just yesterday’s. The trending and exclusively backward-looking approach to interpretation pose more serious problems. There is no command in the Constitution that fundamental rights must be determined by a static past. That philosophy is a personal interpretative decision. It also boldly assumes that today’s courts are capable of making historical and psychological interpretations of prior mindsets with infallible and unbiased precision. And if that task somehow were feasible, the approach would then bind today’s electorate to archaic understandings that American history often left behind and to views espoused by ancestors who could not possibly be elected today.

Our past has been appropriately superseded when it comes to our self-comprehension. Just as we have progressed in science and industrialism, so too have we exponentially advanced in our understanding of our humanity, often at great national pain. We the People are better today.

The current political rhetoric supporting the strict form of originalism often sidesteps a largely undisputed premise central to these points—namely, the Constitution protects fundamental rights existing beyond its limited text. Legal scholars of all persuasions understand that point as an axiom, though they then disagree about what comes next in determining the nature of those rights. But the public dialogue within the Beltway and at statehouses still frequently overlooks the basic point that the Constitution acknowledges rights beyond its express words.

The very choice of words within the Constitution confirms the existence of rights beyond its text. The terminology within the Bill of Rights (in instances where it identifies rights) is about the rights, not the granting of them. Congress shall make no law that abridges “the freedom of speech,” “the press,” or “the free exercise of religion.” We have “the right” to jury trial and “the right” to keep and bear arms. Where the Constitution does not explicitly delineate rights, it embeds them in broad concepts of liberty, privileges and immunities, and more.

Without those concepts, we could conceivably find ourselves without the protection of much that we take for granted—such as our rights to vote, raise children, have sanctity in our homes, marry (irrespective of race), travel, and more. Much more than an inkblot, the Ninth Amendment outright directs that “the enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.” And nothing textually limits rights to 18th or 19th -century norms. Desegregation in federally regulated Washington, D.C., came from the Court’s 1954 decision in Bolling v. Sharpe, which was based on the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause ratified in 1791.

The Supreme Court confirmed as recently as 2015 that the past is only an interpretative guide, not a directive. Faithful application of text (where it exists), contemporaneous context, history, advancements in human understanding, today’s context and norms, and proper use of the many well-honed tools of interpretation in the hands of the constitutionally appointed courts—all those and other considerations have informed and influenced how the law has developed in our history. When construing rights, the Constitution thus permits consideration of today’s wisdom and human understanding. That approach is the far more democratic one than looking solely backward.

No one alive today—let alone their grandparents’ grandparents—elected anyone from the 18th or 19th centuries. Our ancestors gifted us a remarkable constitutional framework. But we have no immediate voice in any lawsuit in which a court would assume that impossible role of discerning and applying ancient mindsets to modern conditions. Our courts need to be able to act in accordance with the society in which they exist. They should use all available tools, which should respect the past but must include the thoughtful consideration of our more advanced understanding of humanity. This approach embraces courts as the independent constitutional branch they are supposed to be, with judges selected through deliberative processes.

We should understand the Constitution as conferring upon our courts a national imprimatur to judge for today, not just for long ago.

John J. Hamill

John J. Hamill is a trial lawyer based out of Chicago who has practiced in courts across the country since graduating from Harvard Law School in 1993. His writings urge that Americans should look ahead to better civil discourse that starts with a mutual acceptance of the actual facts. He can be found on Twitter and on Medium. He has contributed to Smerconish and other publications, including recently the Chicago Sun-Times.