Today abortion is a partisan issue. Most Democrats think that abortion should be legal while Republicans think that it should be illegal. But it was not always this way – at the time of the Roe v. Wade decision in 1973, partisan differences were small.

The General Social Survey, a large national survey that has been conducted regularly since 1972, can be used to trace the growth of the partisan divide. The GSS asks whether a pregnant woman should be able to obtain a legal abortion in the following circumstances: if her health is seriously endangered by the pregnancy, if the pregnancy is the result of rape, if there is a strong chance of a serious birth defect, if the family has a low income and cannot afford any more children, if the woman is single and does not want to marry the father, and if she is married and does not want any more children.

The total number of circumstances in which a person thinks that abortion should be allowed can be used as a measure of their general opinion on the subject. In 1972, the average number of such circumstances was 4.0. Since then, there have been some ups and downs, but no clear trend. In 2021, the average was 4.2, showing a minor shift.

There has been some move towards more extreme positions. In 1972, 35% said that abortion should be legal in all six circumstances and 6% said it should not be legal in any. In 2021, support for those positions was up to 47% and 8%. However, even today many people still take an intermediate position – that abortion should be allowed in some circumstances but not others.

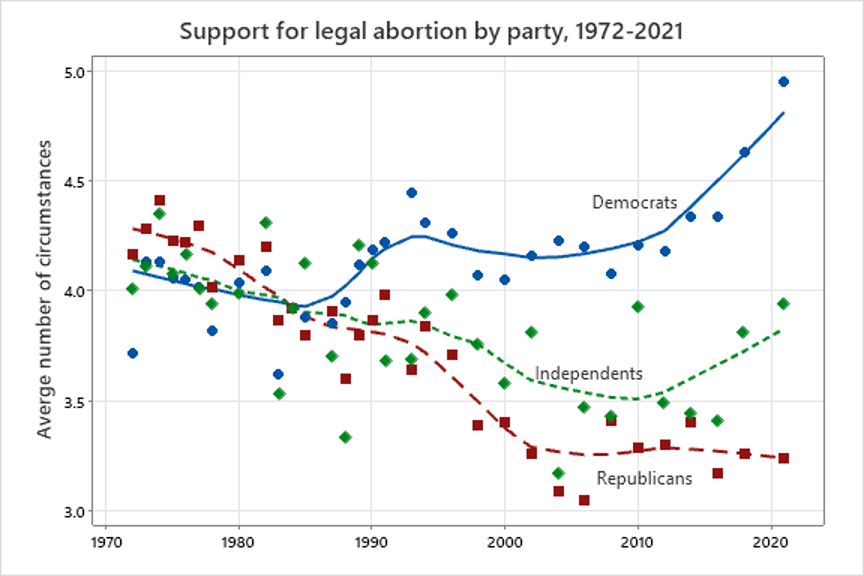

The overall stability hides a striking divergence between supporters of the different parties. Until the mid-1980s, overall support for abortion was slightly higher among Republicans than among Democrats (see figure). Since that time, support for abortion has increased among Democrats and fallen among Republicans, so the gap between Democrats and Republicans has steadily increased.

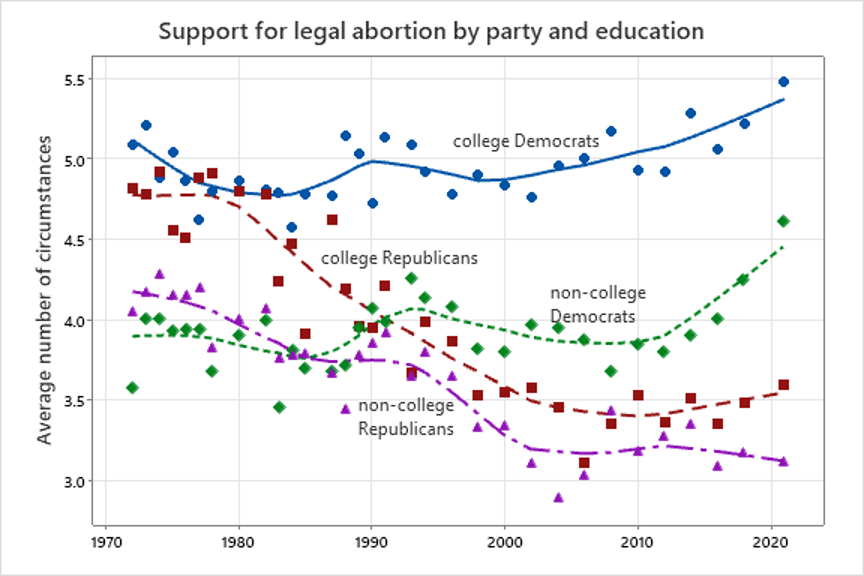

The level of education is also a telling indicator regarding this issue. In the 1970s, there were large differences by education within both parties, with college graduates giving more support to legal abortion (see figure). In the 1980s, support for legal abortion dropped sharply among college-educated Republicans, reducing the educational gap among Republicans. Educational differences among Democrats have remained larger, although they have started to decline since about 2010 as support for abortion has risen among non-college Democrats.

Why did college-educated Republicans turn away from support for legal abortion? Soon after the Roe v. Wade decision, there were calls for a constitutional amendment to make abortion illegal. In 1976, the Republican party platform expressed sympathy, but fell short of an explicit endorsement, saying the party “favors the continuance of a public dialogue on the question and supports the efforts of those who seek enactment of a constitutional amendment to restore protection of the right to life for unborn children.”

The Republican 1980 platform took a clearer position: “We affirm our support of a constitutional amendment to restore protection of the right to life for unborn children.” The 1984 platform went further, repeating support for a constitutional amendment and adding a call for “legislation to make clear that the Fourteenth Amendment’s protections apply to unborn children.”

More educated people generally pay more attention to politics, so it is reasonable to think that they were more influenced by the official party position. In some cases, this meant following their leaders and turning against abortion. In others, it meant changing parties—pro-choice Republicans became independents or Democrats, and pro-life Democrats became Republicans.

What’s striking here is the timing. In 1980, the Republican party opposed abortion and Ronald Reagan won the presidency with the support of religious conservative organizations such as the Moral Majority. But there was no partisan division in abortion attitudes among voters. It took decades for the partisan division among leaders to make its way through the electorate. Indeed, as late as George W. Bush’s elections in 2000 and 2004, there were no clear partisan differences on abortion attitudes among African-Americans, Hispanics, or low-income whites.

Some accounts hold that the growth in political polarization reflects growing divisions in society—between rich and poor, more and less educated people, or residents of urban and rural areas. The trends in the GSS questions suggest a different possibility: that the divergence between supporters of different parties is driven by politicians and activists. After the party leaders grew apart, they were followed by voters who paid attention to politics, and eventually even by those who did not pay much attention. However, even now, voters are much less divided on abortion by party than politicians are.

What does this history suggest about the future? When Roe v. Wade was in force, the debate on abortion was dominated by the question of whether the decision should be upheld or overturned. Now that it has been overturned, political leaders may make more effort to find compromises that appeal to voters with moderate views on abortion.

In this case, public opinion may become less polarized—party members will follow their leaders back towards the middle. On the other hand, there are now many influential activists with strong opinions that abortion should be allowed with few restrictions or that abortion should almost never be allowed.

Given the rise of gerrymandering, fewer members of Congress are in competitive districts. As a result, they may be concerned with appealing to the activists in their party rather than to voters with moderate opinions. In this case, the polarization of the public could continue and even grow stronger.

David Weakliem

David Weakliem was a professor of sociology at the University of Connecticut until his retirement in 2021. He is working on a book about the growth of political polarization in the United States. His writing can be found at http://justthesocialfacts.blogspot.com.

Andrew Gelman

Andrew Gelman is a professor of statistics and political science at Columbia University. His writing can be found at https://statmodeling.stat.columbia.edu.