Before the world saw a video of his horrific death of Ahmaud Arbery, his family and their surrounding Brunswick neighbors were engaged in a fight of a generation: Three prosecutors, two murderers, one camera, zero accountability, and countless thoughts and prayers.

Before Arbery’s case was thrust into the forefront of our national conversation, it had taken weeks for the legal system to respond to his death. Four days following his death, Jackie Johnson, the local Brunswick district attorney, recused herself from prosecuting the case citing that one of the defendants was a longtime investigator in her office until his retirement. Then, more than a month later in early April, George E. Barnhill, another local district attorney who was assigned the case, advised the police that there was insufficient cause to arrest the Arbery’s pursuers and then recused himself citing his family’s proximity to one of the defendants. Nevertheless, the family and community persisted.

Then the graphic video of Arbery’s death emerged and an international audience weighed in, offered support, showed solidarity, and worked around the clock for due process. Organizers helped ensure there was space and capacity to continue building the kind of community where racial terror and state violence could not exist. Coalitions, such as JUSTGeorgia, came together to extend and deepen the impact of this work.

Soon after in early May, the two lead assailants who killed Arbery – Gregory and Travis McMichael – were arrested and booked at the local Glynn County jail. Chris Carr, Georgia’s attorney general, appealed to the Department of Justice to investigate how the case was handled and appointed Joyette M. Holmes, the Cobb County DA and first African-American to hold the position, to be the fourth prosecutor to take the case. Within a week, the autopsy results of Arbery were released, and a third man, William Bryan, was charged.

Despite these amazing efforts, however, the attention faded during the tail half of 2020. National personalities and media headlines moved on to capture the deaths of Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks, and George Floyd. While people were righteously indignant, cities saw summer uprisings while municipal and state leaders solicited the assistance of National Guards, riot control, and tear gas to protect local and state property. State legislators around the country paraded anti-protest policies while prosecutors punished people who were caught protesting after ill-advised curfews.

As we reflect over the year, it is obvious that we still have much work left to do. There were elections won, memories made, and great policies passed. The Civil War-era citizen’s arrest law that motivated Arbery’s assailants was scaled back unanimously by Georgia state legislators. And yet, racial terror and trauma caused by state violence still trigger screams of pain that come from so many people whose bodies lay lifeless in streets across this country.

Celebratory declarations of ‘justice’ in this present moment are shortsighted insomuch as the system in which criminal accountability is considered should never be catalyzed by public outcry nor should due process be limited to those with the power to prosecute or process liability.

Indeed, Travis McMichael, Gregory McMichael, and William “Roddy” Bryan are finally facing criminal charges in the murder of Ahmaud Arbery. It is equally true that Jackie Johnson has not seen equitable repercussions for criminal malfeasance in not only the Arbery death investigation, but also in other wrongful deaths, like the lesser-known cases of Kelsey Rayner, Jerrod Tyre, and even the death of Katie Sasser.

While she herself is no longer in office due to the courageous efforts of Brunswick voters who elected an independent candidate to replace her, she is still able to practice law despite showing on numerous occasions that she is unqualified to be an impartial and objective officer of the court. Meanwhile, George Barnhill the prosecutor who concluded in his official capacity that the McMichaels were justified in their use of deadly force, still remains.

This is a critical moment. The lives of human beings that lay breathless in the streets, jails, prisons, and hospitals of our communities matter. No legal outcome can bring them back, nor fill the void they leave in this world – unspoken visions and unfulfilled dreams.

Faith in America and its democratic principles are waning. More people find themselves distant from the ideals of what makes this nation so allegedly great. Our collective pursuit of true justice, though, can lift us all and usher in a new spirit of hope, love, and freedom. We saw justice in the case of George Floyd; it is time we find justice for Ahmaud Arbery.Before the world saw a video of his horrific death of Ahmaud Arbery, his family and their surrounding Brunswick neighbors were engaged in a fight of a generation: Three prosecutors, two murderers, one camera, zero accountability, and countless thoughts and prayers.

Before Arbery’s case was thrust into the forefront of our national conversation, it had taken weeks for the legal system to respond to his death. Four days following his death, Jackie Johnson, the local Brunswick district attorney, recused herself from prosecuting the case citing that one of the defendants was a longtime investigator in her office until his retirement. Then, more than a month later in early April, George E. Barnhill, another local district attorney who was assigned the case, advised the police that there was insufficient cause to arrest the Arbery’s pursuers and then recused himself citing his family’s proximity to one of the defendants. Nevertheless, the family and community persisted.

Then the graphic video of Arbery’s death emerged and an international audience weighed in, offered support, showed solidarity, and worked around the clock for due process. Organizers helped ensure there was space and capacity to continue building the kind of community where racial terror and state violence could not exist. Coalitions, such as JUSTGeorgia, came together to extend and deepen the impact of this work.

Soon after in early May, the two lead assailants who killed Arbery – Gregory and Travis McMichael – were arrested and booked at the local Glynn County jail. Chris Carr, Georgia’s attorney general, appealed to the Department of Justice to investigate how the case was handled and appointed Joyette M. Holmes, the Cobb County DA and first African-American to hold the position, to be the fourth prosecutor to take the case. Within a week, the autopsy results of Arbery were released, and a third man, William Bryan, was charged.

Despite these amazing efforts, however, the attention faded during the tail half of 2020. National personalities and media headlines moved on to capture the deaths of Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks, and George Floyd. While people were righteously indignant, cities saw summer uprisings while municipal and state leaders solicited the assistance of National Guards, riot control, and tear gas to protect local and state property. State legislators around the country paraded anti-protest policies while prosecutors punished people who were caught protesting after ill-advised curfews.

As we reflect over the year, it is obvious that we still have much work left to do. There were elections won, memories made, and great policies passed. The Civil War-era citizen’s arrest law that motivated Arbery’s assailants was scaled back unanimously by Georgia state legislators. And yet, racial terror and trauma caused by state violence still trigger screams of pain that come from so many people whose bodies lay lifeless in streets across this country.

Celebratory declarations of ‘justice’ in this present moment are shortsighted insomuch as the system in which criminal accountability is considered should never be catalyzed by public outcry nor should due process be limited to those with the power to prosecute or process liability.

Indeed, Travis McMichael, Gregory McMichael, and William “Roddy” Bryan are finally facing criminal charges in the murder of Ahmaud Arbery. It is equally true that Jackie Johnson has not seen equitable repercussions for criminal malfeasance in not only the Arbery death investigation, but also in other wrongful deaths, like the lesser-known cases of Kelsey Rayner, Jerrod Tyre, and even the death of Katie Sasser.

While she herself is no longer in office due to the courageous efforts of Brunswick voters who elected an independent candidate to replace her, she is still able to practice law despite showing on numerous occasions that she is unqualified to be an impartial and objective officer of the court. Meanwhile, George Barnhill the prosecutor who concluded in his official capacity that the McMichaels were justified in their use of deadly force, still remains.

This is a critical moment. The lives of human beings that lay breathless in the streets, jails, prisons, and hospitals of our communities matter. No legal outcome can bring them back, nor fill the void they leave in this world – unspoken visions and unfulfilled dreams.

Faith in America and its democratic principles are waning. More people find themselves distant from the ideals of what makes this nation so allegedly great. Our collective pursuit of true justice, though, can lift us all and usher in a new spirit of hope, love, and freedom. We saw justice in the case of George Floyd; it is time we find justice for Ahmaud Arbery.

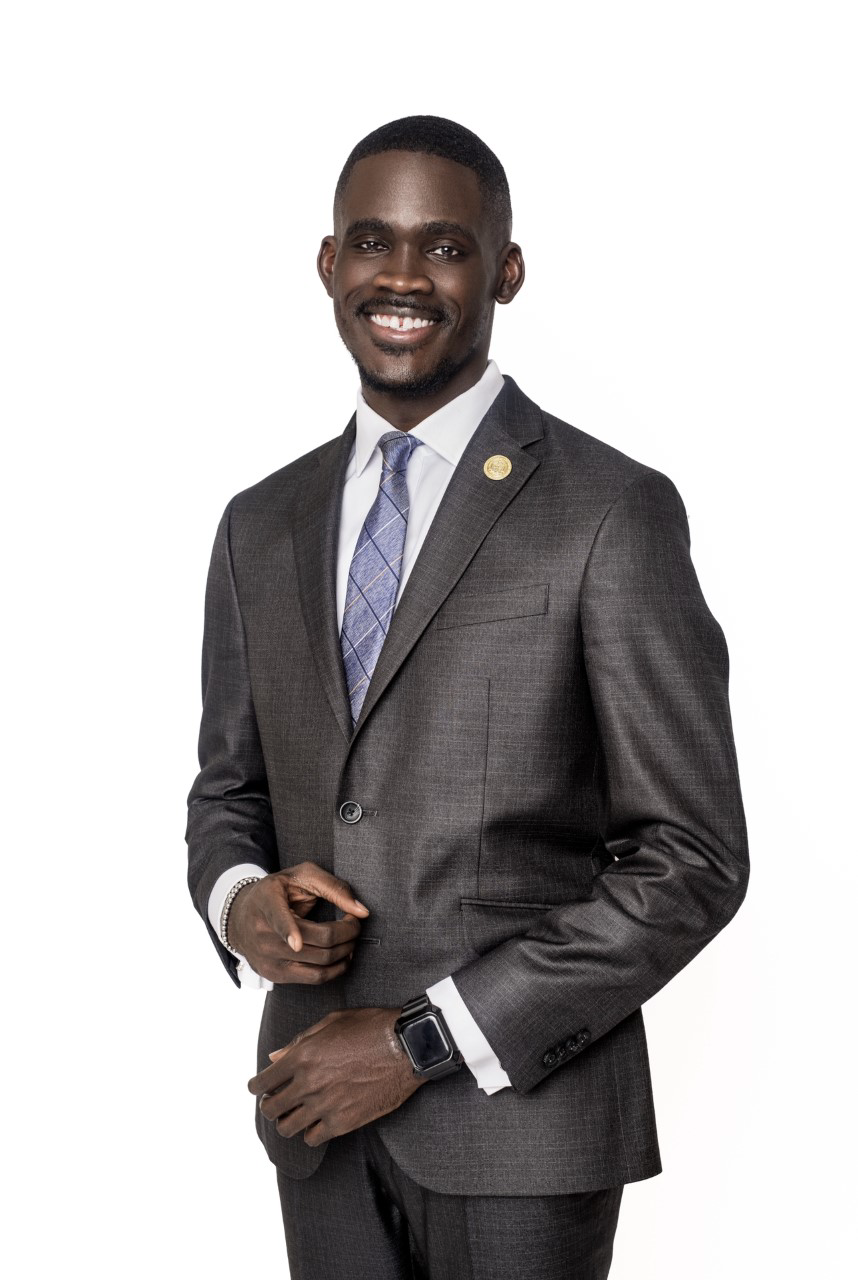

Rev. James Woodall

Rev. James Woodall currently serves as Public Policy Associate of the Southern Center for Human Rights, Founder/CEO of The Major Wish Group LLC and former State President of Georgia NAACP. James is also an Associate Minister at Pleasant Grove Baptist Church in Marietta, Georgia. James also served as an Intelligence Analyst in the U.S. Army Reserve for 8 years. He ran for State Representative in 2016 and served on the State Committee of the Democratic Party of Georgia. He previously served as the deputy campaign manager for Francys Johnson’s (D) 2018 bid for Congress and as the legislative aide to State Representative Miriam Paris (D) for three years in the Georgia General Assembly. James is a Fellow of the second class of the Civil Society Fellowship, a Partnership of ADL and The Aspen Institute, and a member of the Aspen Global Leadership Network.