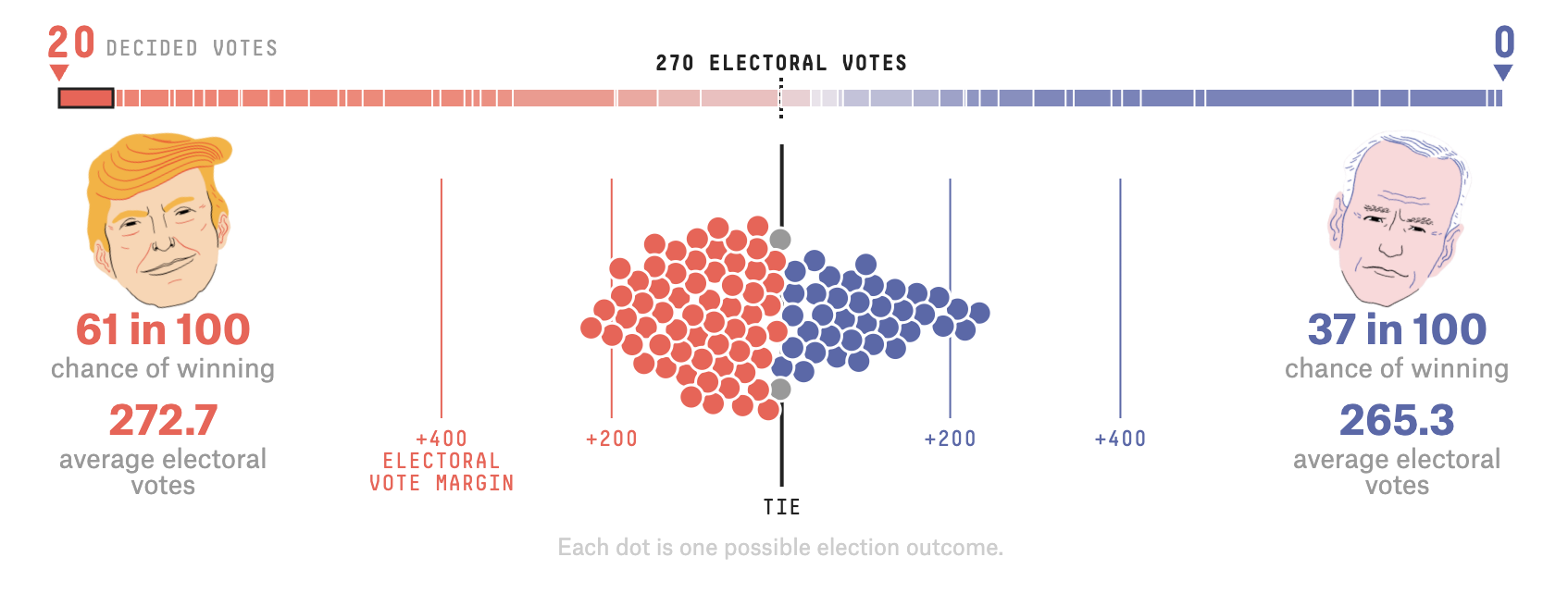

According to FiveThirtyEight’s swing state project, Pennsylvania is the state most likely to be the Electoral College tipping point, thrusting one of the candidates over 270 electoral votes. Without Pennsylvania, Donald Trump has only a one percent chance of reclaiming the White House. With it, his chances jump to 61 percent. Few states wield such political power.

While there is much that Pennsylvania could learn from the rest of the country — say, starting to count mail-in ballots before election day – there is also at least one thing Pennsylvania can teach its countrymen: the virtue of political pluralism.

The Harvard political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt write in How Democracies Die that two of the hallmarks of enduring democracies are democratic forbearance and mutual toleration. In other words, partisan actors ought to avoid playing constitutional hardball – exercising raw power just because they can – out of fundamental respect for the democratic project and acknowledging the legitimacy of their opponent. And as confirmation wars over the past three Supreme Court justices have laid bare, America faces a crisis in both areas.

The courts are but one venue where norm-shattering has left our republic fractured. According to data collected by an ideologically diverse group of political scientists in September, one in three Americans who identify as Republicans or Democrats say violence could be justified to advance their party’s political goals. Moreover, it is increasingly an explicit position of the Republican Party that preventing fellow citizens’ votes from being counted is a legitimate electoral strategy. In fact, The Atlantic reported that Trump campaign officials have discussed “contingency plans to bypass election results and appoint loyal electors in battleground states where Republicans hold the legislative majority.” In a deep-diving article in The New Yorker, reporter Eliza Griswold lays out the numerous strategies through which Republican legislators in Pennsylvania could invalidate mail-in voting.

No matter what happens on November 3rd, it will be up to all of us to pick up the pieces and start doing some serious democracy repair if we want this continental union to endure.

That’s where the historical lessons of Pennsylvania’s past ought to come in and help shape the Commonwealth and the country. The fundamental proposition of William Penn’s Mid-Atlantic experiment was that even in the face of absolute differences, human beings could co-exist and even flourish alongside one another. Many of the first American colonies were founded as religiously homogeneous polities – Maryland for the Catholics and Massachusetts Bay for the Puritans, for example. In Pennsylvania, William Penn purposefully set out to establish a society where, in the words of its 1701 charter, nobody would be “molested or prejudiced” on account of his or her religious beliefs. As the Harvard historian Jill Lepore writes in her seminal one-volume work of American history, These Truths, for William Penn, “Peace rested on tolerance.”

Penn’s religious toleration opened the door to religious pluralism in Pennsylvania, as Lutherans, Moravians, Catholics, Presbyterians, Baptists, and many others flooded Pennsylvania’s shores. Meanwhile, religious intolerance and violence gripped many of Pennsylvania’s sister colonies. William Penn’s experiment proved that a workable, even thriving politics did not require uniform agreement on the highest goods in life. Fundamental differences of opinion need not function as roadblocks to the health and flourishing of the polity.

Fortunately, America’s founders recognized this, as well. Differences were to be expected. As James Madison would later write in Federalist No. 10, “As long as the reason of man continues fallible, and he is at liberty to exercise it, different opinions will be formed.” The choice was between suppressing differences – ensuring uniformity and tyranny – or structuring society to embrace them. Differing on the biggest questions in life (and the afterlife) could either be the cause of enmity and mutual destruction or be channeled as a path towards long-term human flourishing. The former option tells much of the story of human history. The founders opted for the latter.

Today, we are blessed with immense religious diversity here in America, but our differences in religious opinion no longer provide the bulk of the fuel for our mutual contempt. Politics does. As our partisan divisions increasingly capture deep-seated tensions and differences running along the ever fraught lines of identity, the all too human impulse to “other” our fellow citizens has transferred out of the religious space and into the political sphere.

Then, it is essential that we consciously follow in Penn’s footsteps by affirming the principles of political toleration and pluralism. As Thomas Jefferson said in his 1801 inaugural address:

“[H]aving banished from our land that religious intolerance under which mankind so long bled and suffered, we have yet gained little if we countenance a political intolerance as despotic, as wicked, and capable of as bitter and bloody persecutions.”

Of course, pluralism must have its limits. Even as we embrace the politics of pluralism, we must agree upon some minimum moral consensus. Indeed, the founders did not, and a bloody Civil War had to be fought decades later to forge such an accord. And although the founders may have done much to calcify inequality and even human bondage, they set into motion a constitutional order that offers Americans the promise, each day, to realize a union more perfect than that of the day before.

And as we perfect our union, certain constraints must be honored. Our founding ideal, embedded in the preamble of the Declaration of Independence, provides us with a principle that must not be up for debate: the inherent dignity of the individual. As such, we cannot tolerate politics that run roughshod over these basic precepts of individual human dignity.

Advocating pluralism is not a call for political meekness or watered-down centrism but rather a plea that even as we vigorously advance our ideals and policies, we view the other stakeholders in our political system as fellow citizens – people with legitimate points of view and inalienable rights, not enemies that need vanquishing.

Frequent use of hardball tactics over the past several years may compel specific institutional reforms to level the playing field even as it risks initiating an escalating cycle of tit-for-tat

But at the end of the day, no amount of institutional reform will restore the mutual toleration on which a democratic polity must rely. No, the work ahead must center in the hearts and minds of a citizenry committed to the idea of e pluribus unum – ‘out of many one.’ Only we, the people, can carry out that essential work.

The founders recognized this. To James Madison, American constitutionalism rested on the idea of civic friendship, the ability of citizens to reason together away from self-interest, and towards the common good. “Is there no virtue among us? If there be not, we are in a wretched situation. No theoretical checks, no form of government, can render us secure,” Madison argued as he defended the proposed Constitution from charges that its structure would not prevent every evil.

For him, the linchpin of the constitutional project was not the elite but the broader citizenry:

“If there be sufficient virtue and intelligence in the community, it will be exercised in the selection of these men,” he contended at the Virginia ratifying convention in 1788. “So that we do not depend on their virtue, or put confidence in our rulers, but in the people who are to choose them.”

Alas, we are those people. It is our virtue upon which our democratic republic rests. The dishonesty, duplicitousness, and bad faith so endemic among our elected officials cannot be an excuse to stoop to that level in our own lives. Our responsibility is to hold our politicians accountable both through elections and through ongoing civic engagement. In so doing, we can reclaim the pluralist ideals baked into our Constitution and enter a period of political and civic renewal.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________