As soon as rapid COVID-19 testing technology became available, the White House began regularly testing its staff. Reports were that anyone coming in contact with the president required a negative test before being allowed in his orbit. Recent reports have shown that these measures did not go far enough. The President and a sizable portion of his staff – from senior policy advisors to lower-level aides – have contracted the virus. It’s time for Americans to learn how COVID-19 tests work (or don’t).

How Does EUA Differ from Normal FDA Approval?

On January 31, 2020, Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Alex Azar declared a Public Health Emergency due to “confirmed cases of 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV).” That declaration triggered a separate order to enable the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to issue Emergency Use Authorizations (EUA) as long as other statutory requirements were met.

A normal FDA approval process for a diagnostic test requires a complex application. When companies present a new test under normal circumstances, they must report their test’s diagnostic accuracy. This measures the agreement between the new test and a standard test, which the FDA defines as “the best available method for establishing the presence or absence of the target condition.”

The most basic test that the medical community agrees on measures sensitivity and specificity. The sensitivity is the proportion of people with the disease that test positive; the specificity is the people without the illness that test negative. To determine test accuracy, a company needs to choose the number of people or specimens to be tested, who should perform the test, and the conditions under which it is performed. The FDA recommends tests across the entire range of disease states, including people with other conditions that could confuse test results, and people from different demographic groups. It is essential to reflect the device’s real-world use, particularly for a point-of-care test performed outside of the laboratory by those caring for the patients. Again, the FDA recommends multiple users with a range of training and experience.

How many people need to be in the study? It depends on how many participants that researchers expect to have the condition and whether they are examining a screening test or a diagnostic test. A 2016 study from the Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research calculated statistical tables researchers could use. They provide two examples. The first was a screening test for obstructive sleep apnea, assuming that 80% of people screened will have the condition. Researchers would need to test at least 61 subjects, including 49 who have the condition. The other was a diagnostic test for eye disease in newborns that occurs in about 20%. Researchers would need to examine at least 535 infants, including 27 with the disease.

A product approved under an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) will, by definition, not meet the usual FDA criteria. Tests considered for an EUA “may be effective” to diagnose the agent identified in the Public Health Emergency declaration. The FDA Commissioner determines that the potential benefits of the diagnostic test outweigh the potential risks of inaccuracy. This “may be effective” standard is much less stringent than the usual “effectiveness” standard. An EUA can only be approved when there is no adequate, approved, and available alternative test. The data submitted to support the product’s use can be “published case reports, uncontrolled trials, and any other relevant human use experience.”

EUA approvals are based on many factors – including how the product serves a significant unmet need, the urgency of that need, the serious and incidence of the clinical disease, and manufacturing capacity.

The statute governing EUAs replaces the typical lengthy instructions for use with a “Fact Sheet” that manufacturers should design for people who have “the most basic level of training.” This machine could be operated by a medical assistant with training awarding a certificate after high school graduation. The FDA recommends – but does not require – manufacturers to develop the more detailed information we typically consult before using a product the first time. The FDA is further authorized to establish appropriate conditions for the test’s performance, such as whether it is processed in a laboratory or on the spot – known as “rapid testing” or “point-of-care testing.”

The Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act that governs EUA also allows the Alex Azar, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, to provide immunity from liability claims.

To summarize: The tests that we as a nation currently rely on don’t meet the usual stringent FDA approval processes – they “may be effective.”

Tests for SARS CoV-19

There are two ways to detect the virus: molecular tests and antigen tests. The third testing modality, antibody testing, only detects previous exposure and does not diagnose a current infection.

A molecular test identifies genetic material from the virus, usually from a nasal swab. An antigen test detects specific proteins on the virus surface. Results from antigen tests are typically available in an hour or less. If this test has a positive result, the person likely has an active COVID-19 infection. However, the false-negative rate is high.

Abbott announced its ID Now rapid test on March 27, 2020, and President Trump promoted it, displaying it in the Rose Garden a few days later. The initial data provided said that the test was conducted by obtaining nasal swabs from people with mild respiratory symptoms and then “spiking” them with the virus. These are called “contrived clinical nasopharyngeal swab specimens.” (Nasopharyngeal [NP] samples are obtained by placing a swab high up in the nose.)

For these simulated patient samples, the company had no real patients it could test with an alternative standard for comparison, so it determined the lowest concentration that was detected 95% of the time (19/20 samples). To check potential cross-reactivity with other viruses, the company did a computer simulation that showed no false results.

In May, Abbott announced an interim analysis of data from a single urgent care center in Washington that tested 256 patients. ID Now identified 29 of 29 positive samples and 226 of 227 negative samples when confirmed with the laboratory molecular PCR test. Patients were tested an average of 4 days from symptom onset – 90% tested within seven days. Abbott does not describe the test as a screening test or diagnostic test, simply a means for “detection of nucleic acid from SARS-CoV-2.”

Three peer-reviewed studies now published in reputable journals, all from New York institutions, found that the ID Now test had a high false-negative rate – missing between a quarter and a third of patients who were infected with SARS-CoV-2. These results compared with the initial report from Abbott’s press release that 226 of 227 negative samples were confirmed just doesn’t make sense. I am anxious to see the final peer-reviewed published data of Abbott’s sponsored study.

The Abbott ID Now is the test used in the White House.

When Does a Test Come Back Positive?

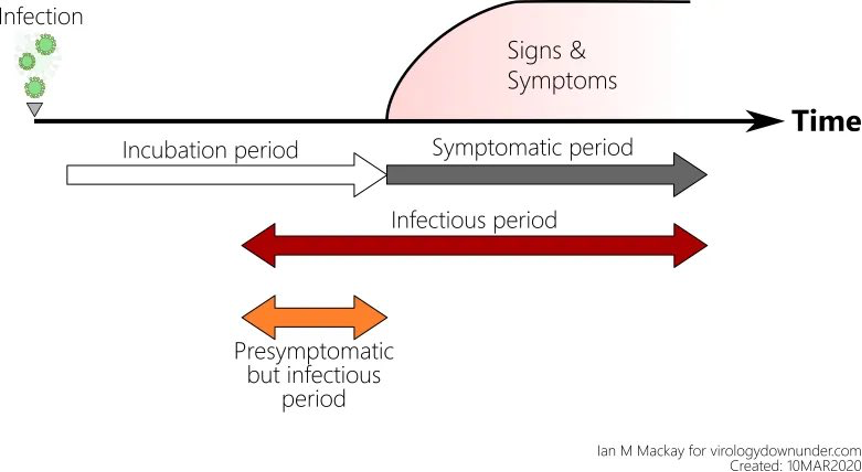

There is another problem with testing. It has to do with figuring out the relationship between exposure to the virus, the time the virus incubates in the body before the person shows symptoms, when a person can infect others, and when the tests will come back positive. This problem is particularly concerning because we now know that people are contagious in the days before symptoms appear— before they know they have the virus. Plus, people who do not develop symptoms — asymptomatic carriers — are infectious and don’t know it. While the virus’s behavior is variable, the typical timeframe from infection to symptoms is a median of five days, according to Dr. Anthony Fauci.

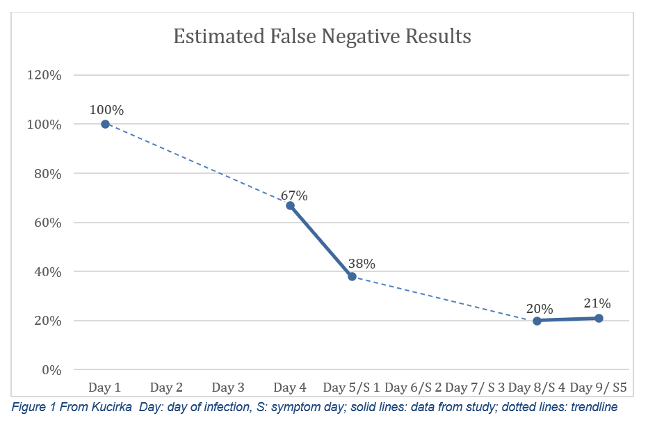

The frightening aspect of the rapid SARS CoV-2 tests is that they have been used to “clear” people – whether it is exposed healthcare workers returning to the bedside or members of our government. Researchers at the National Institutes of Health have been working on a model to calculate an estimate of false-negatives that can be expected based on the day of symptoms and the day of estimated infection. The article provides a detailed statistical model and a link to their open-source coding. They are continually updating the model as more reliable data are published.

Four days before symptoms appear, test results are expected to be 100% negative despite infection because there is not enough virus to detect. The false-negative rate moves to 67% the day before symptoms appear, and 38% the day the person is symptomatic. The false-negative rate reaches its lowest on days 8 and 9 of infection (or days 4 and 5 of symptoms), around 20%.

In the “typical” case profile, the false-negative rate is 67% the day before symptoms appear. This modeling does not even consider the variability in the skill of the person performing the portable test and how carefully the machine is maintained outside a traditional medical laboratory.

The Pandemic Challenge

This is the pandemic dilemma in a nutshell. The virus is new, so there is no standard test to detect it. The government is in a hurry to get tests out there, so it authorizes tests that may be effective. Companies, understandably, want to get to market as soon as possible to outpace their competitors. With the watered-down requirements, it is easy to get a test approved quickly in this environment.

Laboratory-based tests take longer to perform. They are more complex, require chemicals that may or may not be available, and professionals with college degrees and specialized credentials perform them. There has, understandably, been frustration that test results can take a week or more to come back. This process must improve as we approach the high-risk influenza season.

COVID Test Negative? Don’t Bet Your Life on It

Enter the rapid test. One of the ID Now test system’s major selling points is that results are available in less than thirty minutes. It’s enticing to be able to go to the walk-in center and leave with your result in hand. But, how many people know that the trade-off for the quick result is a reduction in accuracy?

Update—37 positive 1 week WH-orbit #COVID19. *6 New:

Hicks

D&M Trump

*Stephen Miller

*2x military aides

4x WH press aides (*Drummond)

*C Ray

McEnany

Conway

G Laurie

C Christie

M Lee

T Tillis

R Johnson

R McDaniel

J Jenkins

B Stepien

N Luna

1x Jr staffer

3x reporters

11x OH staff pic.twitter.com/5dBoJvMG2Q— Eric Feigl-Ding (@DrEricDing) October 6, 2020

Suppose the White House tested everyone who attended the reception for Amy Coney Barrett, participated in debate prep, and otherwise had close contact with the president. They relied on negative results as proof no one was infectious, so they apparently decided masks were not needed. There are, as of this writing, according to Dr. Eric Feigl-Ding, a Harvard and Johns Hopkins-trained epidemiologist, 37 people who’ve gotten a rude awakening I’d wish on no one.

Peer-Reviewed Published Studies

Three studies examining test accuracy were published in the peer-reviewed medical literature. All were published in July and conducted in New York — in the Northwell Health System, Columbia University, and New York University. They compared the Cepheid Xpert Xpress for SARS-CoV-2, the Abbott ID Now, and the GenMarkDx ePlex SARS-CoV-2 test.

Researchers at Northwell Health evaluated the analytical, clinical performance, and workflow of all three devices. Of the 108 samples, 88 were initially tested on the ePlex then frozen for subsequent testing. Twenty were processed fresh on each platform. The authors note that samples were from symptomatic patients of all genders and ages, but do not state when the specimens were collected in relation to the start of symptoms. All samples were processed according to manufacturer’s’ instructions. They reported three metrics: analytical sensitivity, clinical performance, and workflow characteristics.

Researchers measured analytical sensitivity by a limit of detection (LoD), which measures how much of the virus needs to be present for the test to come back positive. The Xpert Xpress needed 100 copies of the genetic material per milliliter of fluid to be detected, ID Now needed 20,000 copies, and ePlex needed 1,000. This contrasts with ID Now’s stated LoD of 125 as the lowest level detected 95% of the time. Each was different from the manufacturer’s data.

In the absence of a perfect reference standard, a test’s performance is evaluated against an imperfect reference standard expressed as a positive percent agreement (or PPA and a negative percent agreement (NPA).). All had an NPA of 100%, meaning that all negative samples were correctly identified as negative. Xpert Xpress had a PPA 98.3%, ID Now, 87.7%, and ePlex, 91.4%. The PPA measures what percent of true positives were detected. If you flip it and subtract from 100, that means the Xpert Xpress missed about two positives; ID Now missed about 12, and the ePlex, about 9. Put another way, Xpert Xpress detected four positive results missed by the other two and one more for each of the other devices.

In the workflow analysis, Xpert Xpress’s hands-on time was about 1 minute per sample. ID Now and ePlex took 2 minutes. Run time for Xpert Xpress was about 46 minutes, ID Now, about 17 minutes, and ePlex, 90 minutes. ID Now tests one sample at a time. The other two devices can add modules or bays for simultaneous, more efficient testing. Assuming the test prep, run time, and disinfecting between tests take 30 minutes for ID Now, one unit could handle 48 tests daily. The Xpert Xpress takes about an hour per sample or 24 tests daily. Therefore, the two-module unit would allow 48 tests per day; the four-module unit would allow 96.

Researchers at Columbia University compared the performance of the ID Now device with the Xpert Xpress. Researchers used samples that had already been tested in the laboratory to ensure a variety of positive ranges (high, medium, and low viral load) and negative.

Overall, the PPA of ID Now was 74%, while Xpert Xpress was 99% of the 88 samples. Put another way: the ID Now tests missed about a quarter of true positives. Furthermore, the device had the most trouble with low viral loads, detecting only 34% of the known positive samples. The Xpert Xpress identified 97%. Both machines detected all of the medium and high viral loads and the 25 negative specimens.

The authors note that Abbott modified ID Now’s instructions to remove the recommendation that swabs be placed into tubes containing liquid. This change could be due to a supposition that the fluid was deleting the amount of virus to the point that it was not detectable.

As I watched the news coverage since the president’s positive diagnosis, the most common rapid tests mentioned were the ID Now’s performance against the Xpert Xpress. Considering the change in instructions, researchers tested both dry samples and those placed in tubes with liquid.

What makes this study different from the others is that these researchers collected specimens from patients in the ED and analyzed them within 90 minutes of collection. The initial 15 samples placed in liquid, according to original instructions, had a positive percent agreement of 67% (meaning 33% of positives were missed). The ID Now detected 17 positive results on dry swabs when the Xpert Xpress detected 31. Negative results matched 69 of 70.

These authors recommend the ID Now as a screening test to “rule in” the diagnosis. That means if the result is positive, it can be considered accurate. However, when the patient was positive, the number of reported negative results was too high to use this device to “rule out” a SARS-CoV-2 infection or confirm someone is disease-free. Of note, Abbott disag

reed with these findings. The company continues to point to results from an Abbott-sponsored study in Washington state. Still, the results have not been published in a peer-reviewed journal, only in a press release.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________