When the COVID-19 pandemic hit the globe and lockdowns were imposed in early 2020, U.S. steel firms responded to plummeting demand with production cuts. But then, as vaccines rolled out and the economy reopened, demand from steel end-users firmed up. Domestic supply did not keep in pace with increased demand, and President Trump’s Section 232 tariff of 25% on steel imports further limited supply.

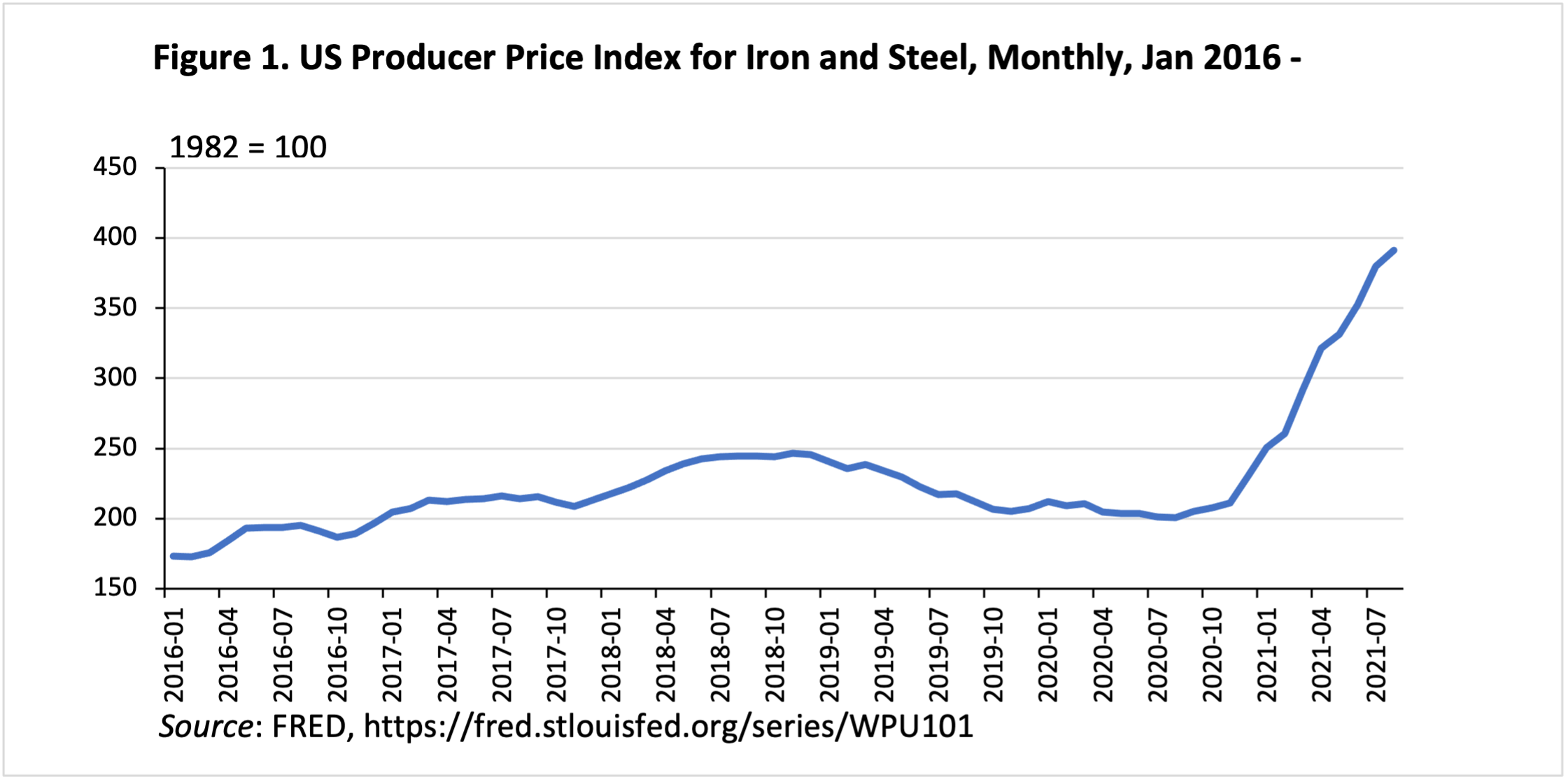

As a result, U.S. steel prices started to trend upward in September 2020 (Figure 1). Over the first eight months of 2021, U.S. producer prices jumped by almost 70%. Steel mills took advantage of the skyrocketing prices. Nucor Corporation registered the highest quarterly earnings in company history in the second quarter of 2021, and US Steel also delivered record-adjusted EBITDA margins (earnings before interest, income taxes, depreciation, and amortization). ArcelorMittal reported operating income of $2.6 billion and $4.4 billion in the first two quarters of 2021 – the best quarterly and half-year results the firm has reported since 2008.

The bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, recently passed by the Senate, promises $550 billion in new federal investment in America’s infrastructure, including $110 billion for roads and bridges, $66 billion for railway, $39 billion for public transit, $25 billion for airports, and $17 billion for ports. Construction-heavy projects over the next several years will further benefit US steel producers – all good news for steel firms and giving joy to the AFL-CIO, a long-time advocate of protection for steel jobs.

However, Trump’s Section 232 tariffs present a problem for President Biden: They do not make sense for the wider economy. The steel industry employs roughly 140,000 workers, but about 6.5 million people work in steel-consuming sectors.

Trump’s tariffs, along with a vast array of anti-dumping and countervailing duties, protect the profits of steel firms, and the welfare of a small number of steelworkers. But these benefits come at the expense of a much larger group of downstream industry jobs gouged by high steel prices. Increased steel prices put downstream U.S. manufacturing firms at a disadvantage relative to their foreign competitors. A previous estimate suggested that steel users pay an extra $650,000 for each steel mill job saved.

Despite Trump’s argument that Section 232 tariffs must be upheld for national security, the argument has very little credibility. Before the tariffs took effect in 2018, Chinese steel products had already been almost entirely excluded from the U.S. market by antidumping and countervailing duties. Later, the U.S. government took a bilateral approach to negotiate with trading partners on the steel trade. As of now, Canada, Mexico, and Australia are exempt from the Section 232 steel tariffs. Korea, Argentina, and Brazil secured agreements with the U.S. on export quotas.

As a result, the European Union and Japan are the remaining key suppliers of steel products to the United States. Both close U.S. allies, they are the two largest steel exporters to the US market. Furthermore, the EU and Japan, together with Taiwan and China, are the economies mainly targeted by Trump’s extended tariffs on derivatives of steel imposed in January 2020.

In May 2021, the U.S. and the EU started discussions on how to address global excess steel capacity and resolve their dispute, launched in the World Trade Organization, on US Section 232 tariffs. At the US-EU summit one month later, the two sides agreed to resolve the issue by the end of 2021. However, the American Iron and Steel Institute warned that Washington should “maintain strong and effective trade measures to prevent surges in steel imports from around the world that could quickly undermine the U.S. industry and our national security.” No doubt these sentiments are applauded by the AFL-CIO, which enjoys an outsized voice in President Biden’s trade deliberations.

Thanks to the conflict between foreign policy priorities, the broader interests of the US economy, and the political heft of the steel lobby, the Biden administration faces a political headache. On one side, U.S. steel firms and unions want the tariffs to remain in place. On the other side, US manufacturers who consume steel, along with EU and Japanese exporters, demand that the tariffs be lifted.

The question is whether Biden can make peace with organized labor and eliminate the tariffs before the November 2022 Congressional elections, or whether domestic politics keeps them in place at least until 2023, and perhaps longer.