Image by Steve Winter and National Geographic

How do you grieve for a mountain lion?

In a world where social media can both unite and divide us, with the tragic death of Los Angeles’ beloved mountain lion, known as P-22, the online world presented their very best, with people around the globe tweeting and posting, united in grief and showing compassion for a lonely and heroic cougar that meant so much to so many. Governor Gavin Newsom shared that he “grew up loving these cats,” Hilary Duff wrote on Instagram that “P-22 = Icon,” and Rainn Wilson tweeted, “RIP to P-22, a gorgeous LA icon.” Media outlets as diverse as Rolling Stone, CNN, The Economist, NPR, and Buzzfeed featured his passing, and the day he died, P-22 was trending on Twitter.

This may be the first time in history that a mountain lion took over the internet.

Yet perhaps the question many of those not already in the P-22 fan club are asking is, why would the world mourn a mountain lion?

For those confused by the bizarre term “P-22” popping up as a Twitter trend last week, to start to understand the widespread grief, you must first know this mountain lion’s story. P-22 lived for over ten years under the Hollywood sign, surviving against all odds in the second-largest city in the country and the smallest know home range ever recorded for a male mountain. So often called (by me) the ‘Brad Pitt of the cougar world’—they are both ruggedly handsome, beloved around the globe, and challenged with their dating lives—he is the classic Hollywood underdog or unlikely hero. It’s the puma version of Rebel Without a Cause— “a rebellious young man with a troubled past comes to a new town, finding friends and enemies”—with maybe a bit of The Big Lebowski thrown in.

To get to Griffith Park, P-22 made a miraculous journey in 2012 and crossed two of the busiest freeways in the country to make his home in Griffith Park. But he didn’t really have a choice. Mountain lions are solitary creatures and live alone. Males will often fight to the death over territory. So, when he came of age, he faced a tough choice to survive: either certain death by an older mountain lion if he stayed put, or likely deadly peril by crossing some of LA’s infamous freeways. He chose the freeways, and somehow, unlike many of his relatives in the area who are killed crossing these roads, he made it. This is the stuff that Hollywood blockbusters are made of –the journey of the hero.

Stand overlooking the 405 for a few minutes, day or night, and try to cross. I dare you. Well, not really, because it’s illegal. And also extremely foolhardy—this ten-lane freeway never quiets, even in the middle of the night. Yet P-22 somehow made it across not just that freeway, but also an equally as menacing one, the 101.

Once he entered Griffith Park in 2012, he stayed until his death last month, coexisting with the over 10 million park visitors a year, and remaining largely unseen as befitting his species nickname, “ghost cat.” Occasionally he made an appearance on the Ring doorbell cam of one of the homes surrounding Griffith Park—the footage from these encounters was widely shared on social media with the same excited and reverent tones a devoted fan would use upon meeting Mr. Pitt. He had his share of celebrity scandals, like when he decided to make a meal of a koala in the Los Angeles Zoo or take a nap in a crawlspace of a home in Los Feliz, but both were met with Los Angeles doubling down on their support for his large predator remaining in their midst—the Zoo apologized for their fences being too low. The couple who owned the home where P-22 squatted for an evening said, “we have two cats and would gladly make room for a third.”

If you live in California, the odds are almost 50/50 that you live in mountain lion habitat. Along with technology and sunshine worship, wine tasting, and beaches, one could argue that the mountain lion also stands as a testament to the California value system. Admittedly it’s a more complex value than promoting the merits of surfing or Napa’s fine vineyards, but nonetheless, Californians have proven they love their cougars. That P-22 prospered in Hollywoodland is just one example of our affection toward the cat.

This affection for mountain lions isn’t cursory. In 1990 California residents passed Prop 117 by ballot measure. The act, known as the California Wildlife Protection Act, reclassified the lion as a “specially protected mammal” and banned the sport hunting of lions in the Golden State. And for good measure, the vote even included a $30 million-dollar allocation to acquire critical habitat for mountain lions and other wildlife. No other state in the country prohibits the hunting of lions.

The Act had a long history, but it began with the outrage of an artist, Margaret Owings, over the killing of a single lion near her home in Big Sur in 1962. As the history books put it, “she lit the fuse with a phone call.” Her phone list was quite impressive–she formed a committee with Ansel Adams, Rachel Carson, David Brower, and Teddy Roosevelt’s nephew. In the 1980’s she rallied Robert Redford to the cause, and persuaded her friends Jimmy and Gloria Stewart to encourage their friend, then Governor Ronald Regan, to join the cause. Governor Newsom’s father was also instrumental. Coincidently, the protections that safeguarded P-22 came with a Hollywood—and bipartisan— pedigree.

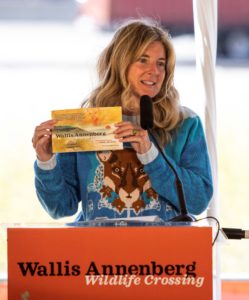

And P-22 also united us, as his plight, trapped by freeways in Griffith Park and destined to become LA’s loneliest bachelor—became a rallying cry for action, supported by most. No matter what political party you affiliate with, no one likes to see magnificent animals like P-22 die on the side of the road, mangled by cars. And because of his story, the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing broke ground this spring outside Los Angeles, supported by Republicans and Democrats alike. This crossing will not only ensure the survival of the mountain lion population in the area but also reconnect an ecosystem for all wildlife and prevent needless deaths on this freeway that 300,000 to 400,000 cars a day use.

This is not just an LA story. Or a California story. P-22, in life and death, has inspired people worldwide to act and build more wildlife crossings in their areas. He helped usher in the “age of wildlife crossings,” galvanizing public support for these projects, including $350 million for their construction in the last Federal appropriations bill.

Yet he also inspired something deeper, for people in Los Angeles and beyond to reexamine our preconception of wildness and what had almost been lost by thinking we needed to banish nature from our midst in our cities. Gregory Rodriguez wrote in the Los Angeles Times a decade ago when P-22 first made an appearance: “I have no illusions that the Glendale bear or P-22 wouldn’t hesitate to dine on me given the right circumstances. But I’m still rooting for them. Deep down, I’m hoping that if they can survive at the margins of human civilization without forsaking their wildness, so can I.”

People connected to P-22 in profoundly personal and meaningful ways. That this holdover from the last ice age could survive under one of the symbols of our age, the Hollywood sign, became a symbol of hope that nature had not yet irrevocably given up on us. His story became a rallying cry, and people worldwide rooted for his survival. That his whole life, he suffered the consequences of trying to survive in an unconnected space amidst urban sprawl, right to the end when being hit by a car led to his tragic end, saddened people across the globe. And the world showing it still wasn’t too cynical or divided to unite around grieving for a mountain lion gave some hope for both the future of wild things—and our own.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Beth Pratt

A lifelong advocate for wildlife, Beth Pratt has worked in environmental leadership roles for over twenty-five years, and in two of the country’s largest national parks: Yosemite and Yellowstone. As the California Regional Executive Director for the National Wildlife Federation, Pratt leads the #SaveLACougars campaign to build the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing, which broke ground on Earth Day, April 22, 2022. The largest wildlife crossing of its kind in the world, it will help save a population of mountain lions from extinction. Her innovative conservation work has been featured by The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, BBC World Service, CBS This Morning, the Los Angeles Times, Men’s Journal, The Guardian, NPR, AP News, and more.

Di Angelo Publications released her book, I Heart Wildlife: A Guided Activity Journal for Connecting With the Wild World, in 2020, and Heyday Books published When Mountain Lions are Neighbors: People and Wildlife Working It Out In California in 2016. Her new book, Yosemite Wildlife, will be published by the Yosemite Conservancy in 2024. Beth has also contributed essays to the books The Nature of Yosemite: A Visual Journey, and Inspiring Generations: 150 Years, 150 Stories in Yosemite. She also has given a TEDx talk about coexisting with wildlife called, “How a Lonely Cougar in Los Angeles Inspired the World,” and is featured in the documentary, “The Cat that Changed America.”

Beth spends much of her time in Los Angeles, but makes her home outside of Yosemite, “my north star,” with her five dogs, two cats, and the mountain lions, bears, foxes, and other wildlife that frequent her backyard.