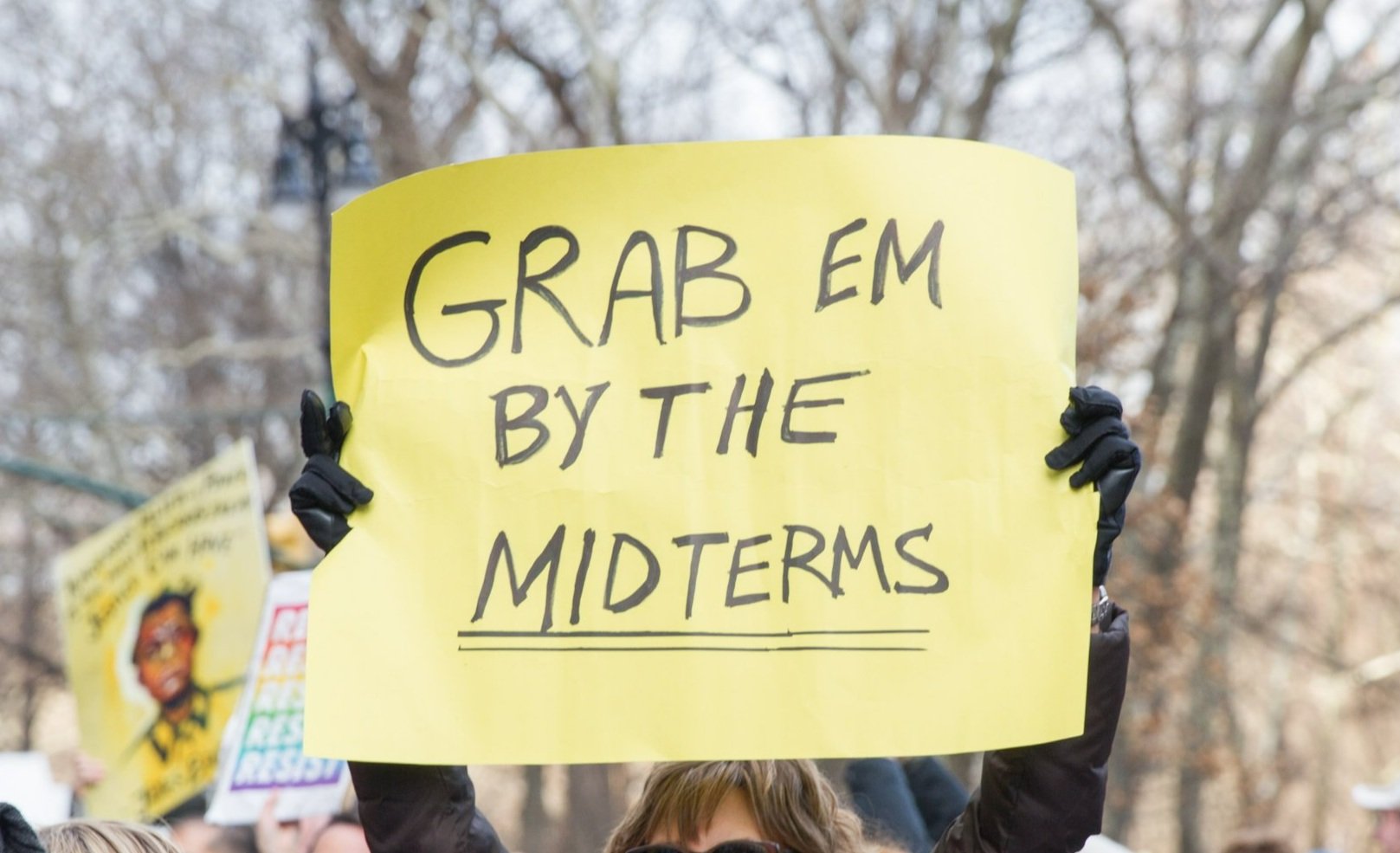

Photo by Mirah Curzer | Unsplash

For almost a year the media and handicappers have predicted that in November a massive red wave will sweep Republicans into office, even in blue states and districts. On the surface, this prediction is reasonable given both that, historically, presidents’ parties have gotten clobbered in their first midterm elections, and that Joe Biden has had consistently woeful approval ratings since last fall.

But these predictions have ignored three factors that might make the 2022 midterm elections different from past. At best, they are premature — and risk skewing coverage of the campaign, thereby affecting voters’ perceptions.

Why might 2022 be different than past midterms?

First, at least since March 2020 when COVID shut down America — arguably since Donald Trump captured the presidency in 2016 — unexpected twists and turns have repeatedly rocked society and politics. As the joke goes, each month seems to produce a verse of “We Didn’t Start the Fire”. From the once-in-a-generation pandemic to the uprisings after the murder of George Floyd, to the January 6 insurrection, inflation like we haven’t seen in four decades, Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade, and most recently, the FBI executing a search warrant on Trump’s home, it seems like something seismic is upending our political sphere every few weeks.

The last two and a half years have taught us to expect the unexpected and understand that we can count only on the political environment to change rapidly. The twists and turns could hurt Democrats as easily as they could help, but this reality means that trying to predict the midterm outcomes months in advance never really made sense. Especially since everyone knew that the very conservative Supreme Court was going to hand down potential blockbuster rulings on some of the biggest culture war issues — abortion, guns, the separation of church and state — in June. Even now, in late August, it seems foolish to think we know how the next three-plus months will go.

Paradoxically, even as our politics fluctuate more than ever, we are also in an era of hardened partisanship: ticket-splitting has become increasingly rare, and few senators and congressmen represent places that the opposite party’s presidential candidate won. That was always going to limit opportunities for Republicans in 2022 because there are no Democratic senators up for reelection in states Donald Trump won in 2020, and only four up for reelection in states where Trump lost by 7.35% or less (by contrast, two Republican-held open seats are in states Biden narrowly won, and a third is in the state in which Trump’s margin of victory was the smallest — North Carolina). In the House, before redistricting, only seven Democrats held seats that Trump had won (though redistricting increased the number of open seats or seats held by Democratic incumbents that Trump won).

These numbers matter. In 2020, many forecasters predicted Democratic gains in the House based on polling, only to see Republicans pick up seats. Why? Because only 16 districts nationwide voted for a congressperson of the opposite party from their chosen presidential candidate. And in the Senate, only in Maine did voters split their tickets and elect a senator from the opposite party of the presidential candidate who won the state (2016 was the first time in the popular vote era in which there were no such splits at all). Yet prognosticators seem to have forgotten that lesson in the face of Democrats polling poorly and the usual midterm itch.

Finally, Republicans have recruited a passel of extremists with questions about their fitness for office or fit for their states or districts— some with checkered pasts — like Pennsylvania’s Doug Mastriano and Mehmet Oz, Georgia’s Herschel Walker, and Arizona’s Kari Lake, to name but a few. These are exactly the sorts of candidates who have lost even in past wave elections favoring their parties. In 2010, for example, these types of candidates cost Republicans several winnable Senate races.

Yet, most of the media ignored these factors — even after the Court overturned Roe, enraging liberals and closing the all-important enthusiasm gap between the parties (in a new NBC News poll, 68% of Republicans and 66% of Democrats expressed a high level of interest in the elections). It was only after Biden and congressional Democrats strung together a series of big wins in July and August, while Democratic candidates scored surprisingly well in several House special elections, and gas prices dropped significantly, that commentators began to contemplate a better November for Democrats. Even Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell acknowledged earlier this month that Republicans might not capture the Senate. And yet, most prognosticators are still painting a fairly grim picture for Democrats — albeit not one without hope.

Why haven’t there been more contrarian voices? The political media is an insular world — reporters talk to operatives in both parties, many of whom share polling tidbits, they consult respected handicappers like the Cook Political Report, and they read each other’s reporting and tweets. So, it’s easy for groupthink to emerge — especially when people in both parties share an outlook on an upcoming election.

None of this would matter if the worst case scenario was the media and forecasters ending up with egg on their faces. That’s nothing new — and it’s part of election prognostication — and the media already serves as a useful punching bag for people on both sides of the aisle (despite the good work done by journalists).

But there is a risk that premature predictions skew coverage of the midterms — and end up shaping the perceptions of Americans less tuned into politics on a day-to-day basis. After all, if they hear that Republicans are going to sweep to victory, they might assume that Democrats deserve this outcome — or they might decide not to vote.

An example of how perceptions shape coverage came earlier in the summer with reporting that Democratic Senator Patty Murray might be vulnerable in Washington state, where Republicans haven’t won a Senate race since 1994. The stories cited new Democratic spending and an internal poll for Murray’s opponent showing a close race. Yet, in Washington’s all-party primary — which often serves as an indicator of how November will go — Democratic candidates scored 55.4 percent of the vote, down from Joe Biden’s almost 58% of the vote in 2020, but significantly up from Murray’s 52.4% in the Republican wave election of 2010.

Murray’s perceived vulnerability came from the idea that a wave was building, but that may not be true. The same holds for reporting on Republican chances in House races in deep blue New England. We haven’t seen similar reporting on Republicans at risk in traditionally, red territory — though that may change after Democrat Pat Ryan won a special election in a swing district last week. But this disparity of coverage could affect where media companies conduct polling, as well as influence fundraising for candidates, the willingness of people to volunteer, or even how much voters engage with local campaigns.

None of this is to say that Democrats will hold the House or gain Senate seats. Redistricting, inflation, and generalized discontent still pose major challenges, especially when it comes to holding the House. But it is to say that the outcome is a lot less certain than most of the media has made it sound — especially after Ryan’s victory signals that the Democratic message can resonate in swing districts. And we’d be wise to avoid such predictions before at least late September when voters start casting ballots. In our current environment, nothing is certain except maybe that turnout and the stakes will be very high.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________