Why Teaching Coping Skills to Our Children is as Important as the ABCs

Growing up, nothing in my home was off-limits to discuss. If you can think of it, we talked about it. My dad, a Vietnam Vet with strong Republican views, and my mother, the center of our family, a grief specialist with a liberal and relaxed approach to life, both gave my twin sister and me the freedom to ask questions, discuss our feelings and experiences openly, without any consequences. We talked about the good, the bad, and the scary and how to manage and work through it.

It wasn’t until high school that I realized my family was unique in this approach to life. So it’s unsurprising to me today that the gap to openly talk about anything has only grown larger in American families.

Last month the CDC released its bi-annual Youth Risk Behavior Survey with some hair-raising statistics. An alarming 42% of high school students reported experiencing persistent sadness or hopelessness, and 22% seriously considered suicide. Our children are screaming at us that they need help.

Despite my safe, happy upbringing, and my own struggles with anxiety and depression as an adult, nothing could have prepared me for witnessing my daughter’s mental health implode.

My 9-year-old daughter has carried the heaviness of anxiety since she was a toddler. When her anxiety showed up, it looked like temper tantrums and sleepless nights. Those two things alone are hard on any family.

Is my child throwing a tantrum because they aren’t getting what they want, or has something triggered their sympathetic nervous system to fight, flight, or freeze?

When little kids experience anxiety, they cannot tell us what the trigger is or why they have great big feelings, so unless we know how to recognize the difference, it often looks like bad behavior. I consider myself lucky because I knew my daughter had anxiety when she was a toddler, and these tantrums were the anxiety manifesting.

Things became trickier as she grew older, and those tantrums became rageful outbursts. I slowly stopped recognizing her behavior as a little girl with anxiety and started seeing a misbehaving child because I couldn’t see what was triggering her. The idea that it was anxiety became muddy as her behavior morphed her into an unrecognizable child. What often seemed like nothing had happened would send her into a tailspin. She also began to experience school refusal in kindergarten, which lasted through third grade. That’s four years of an everyday do-or-die battle to get her into school (or on Zoom). I cannot express enough how school refusal, in and of itself, is a complete soul-crushing experience.

Her anxiety has caused her to jump out of a moving car, run into snowy woods without shoes, break everything in her room, and repeatedly beat me up when I tried to console her. Once, she ran more than half a mile from home, and when I finally caught her, she fought me the entire way back, kicking, screaming, biting, hair-pulling, and yelling at our neighbors that I was kidnapping her.

My daughter was gone. I didn’t recognize this stranger that was showing up more frequently as her anxiety took hold. I couldn’t figure out what I was doing wrong and was beyond heartbroken. How was I going to fix what felt like an invisible problem?

It became a never-ending, uphill battle to find her help, a good therapist, specialists, a (good) child’s psychiatrist, the list goes on, and the waitlists grew.

The breaking point.

In January of 2022, another day of school refusal, this one worse than others. My husband and I pulled into the school parking lot, my daughter fighting like her life depended on it as she wrapped her little arms around a bar under the backseat, where we couldn’t physically move her without hurting her.

That’s when it happened. My sweet 8-year-old expressed that she “just wanted to die.”

In that moment, my world stopped. I had run out of options and ideas. I felt utterly helpless and hopeless.

I was terrified to take her to the emergency room. What if they take her away from me or force me to commit her? I didn’t want her fate in someone else’s hands. As my husband and I sat in the parking lot trying to figure out what to do, he calmly called the ER, explained what was happening, and learned what would happen if we brought her in. We learned they would never ‘take her from me,’ which brought great relief. The hospital suggested that we call the New Hampshire Rapid Response Access Point before we bring her in. At the same moment he was being directed to do this by the hospital, my daughter’s school nurse called me with the same number. She explained that it was a new program that our state started on January 1, 2022, and a mobile crisis team could be dispatched to help manage a crisis.

So, we called.

I’m pretty sure we were one of the first families in the state to use this resource and probably the first with a child as young as eight threatening self-harm. I have never been so grateful for a state program in my life.

The woman on the other end of that call was an angel. Gently walking my daughter through her emotions while she dispatched two individuals from the emergency mobile crisis team. These two incredible humans stood in the freezing cold outside our car for more than two hours, talking to an unresponsive child with such love and care. Slowly she came around and started answering their questions. I sat in the back, holding her. I looked over to my husband in the front, tears rolling down his face, as it suddenly all clicked. All this time, she was suffering from anxiety. She wasn’t ‘acting out’ and ‘fighting authority’ or ‘misbehaving.’ All this time, we were fighting her as though she had a behavioral problem instead of helping her learn to cope.

She was not behaving badly; she was protecting herself the only way she knew and screaming at us to listen through her behavior.

I gently explained to her that she had a boo-boo inside her body. I told her it’s no different from a broken arm, it’s painful, and while we cannot see it, we know it’s there, and we need to find someone who can help make it better. So we decided as a family that if she couldn’t go to school the following day with ease, we would go to the hospital because they have people there who could help.

The following day came, and she tried but couldn’t manage to get to school. This was the second COVID winter, and the ER was like a war zone, with beds in every hallway. For her privacy, we were put in a private room for them to evaluate her. Once that was over, they informed us that they didn’t feel like her life was at risk and said it was more likely that she didn’t understand what “dying” meant, but their recommendation was to institutionalize her. It was ultimately my choice, and I will never be able to describe the heaviness of that decision.

After days of contemplating what to do, what was best for her, I decided not to have her committed. I believed sending her away, when the core of her anxiety was separation and transitions, didn’t seem like the best choice. Instead, I made an emergency appointment with her psychiatrist the following week and decided to put her on a mood stabilizer. This was also a tough decision. But, knowing her and what she’d been living through for years, I felt it was the right choice for her.

In the weeks and months that followed, with the help of the right mental health professionals and caring school staff, my daughter was better than stable; she was happy. We had learned so much about recognizing her anxiety and triggers and teaching her to do the same. In turn, providing calming reassurance. I cannot explain how life-changing it was for our family just to be able to identify what was happening and manage it accordingly. Approaching her with empathy as she was melting down instead of discipline was a game changer, and we were able to teach her coping strategies for herself.

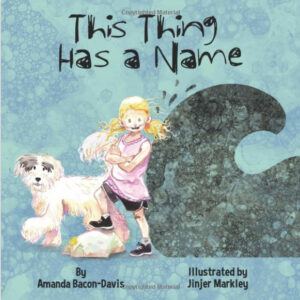

Months later, after a great deal of healing and restructuring our new normal, I was on a family road trip when a book, very unexpectedly, popped into my head. Twenty minutes later, I’d typed it on my phone and emailed it to myself. Eight weeks later, This Thing Has A Name was published—a children’s book about a child’s journey of identifying, normalizing, and taming anxiety.

Immediately a new world opened to me, the sheer number of parents and caregivers who were, and are, experiencing what my family had gone through, shocked me. I never saw other parents at school in the mornings being beaten up because their child had such intense school refusal. I didn’t see other children throwing their water bottles clear across the soccer field, and no one told me that their child had broken everything in their bedroom or run away from home, all because of their anxiety. Suddenly, there was a community of people who needed someone to hear their story and, like me, know they weren’t alone. The stress for caregivers is incredible.

This book is now helping families across the world, and for that, I am happy. Happy my family’s story can be a part of a solution. But for me personally, the best and most unexpected thing to have come from my book was how it helped my daughter, who now truly understands what anxiety means and finds power.

The CDC statistics prove that our children are screaming for help, and we must do a better job at listening to them with proper mental health education and preventative care.

How do we help our children now? The first part is trusting ourselves as parents and caregivers. We know our children best and what their normal looks like for them. When they act outside of that, it may be their way of screaming for someone to notice what’s happening.

One of the greatest gifts we can give our youth is to start the conversation about mental health and coping strategies as early as possible. Working with our children to identify feelings and to be compassionate toward themselves is a life-changing tool. When we teach our children healthy coping strategies and practice them regularly, we build mental muscle memory so that they have a built-in resource if they find themselves in a mental health crisis.

Mental health’s impact on any individual ripples into our families and communities. No one is immune to anxiety, young or old, fleeting or long-lasting; everyone will experience it eventually. However, we can prepare our children by teaching them healthy coping strategies.

Our country needs more resources, not more excuses. I am grateful to Governor Sununu for implementing the Rapid Response Access Point. It saved my daughter and my family. Mental health is a systemic problem, but it can be better managed. By focusing more resources on mental health, imagine the many things that would start to resolve themselves, such as the billions of dollars companies lose yearly in productivity costs, addiction prevention, physical health, crime, and suicide. There isn’t a cure, but we can implement countermeasures now to help move the needle in a direction that makes an impact.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Amanda Bacon-Davis

Amanda Bacon-Davis

Amanda Bacon-Davis is a successful businesswoman, entrepreneur, and a proud advocate for supporting the mental health community. Her debut children’s book, This Thing Has A Name, is a recipient of the 6th Annual National PenCraft Award in Literacy Excellence in Children’s Concepts. She has a beautiful daughter, Ella Rain, two amazing bonus kids (who are wonderful adults), and the most loving husband in the world. Amanda and her family live on the Seacoast of New Hampshire with their dog, Dog-Dog, featured in the book. When she is not writing, Amanda’s favorite thing to do is travel and belly-laugh with her family.

Amanda Bacon-Davis

Amanda Bacon-Davis