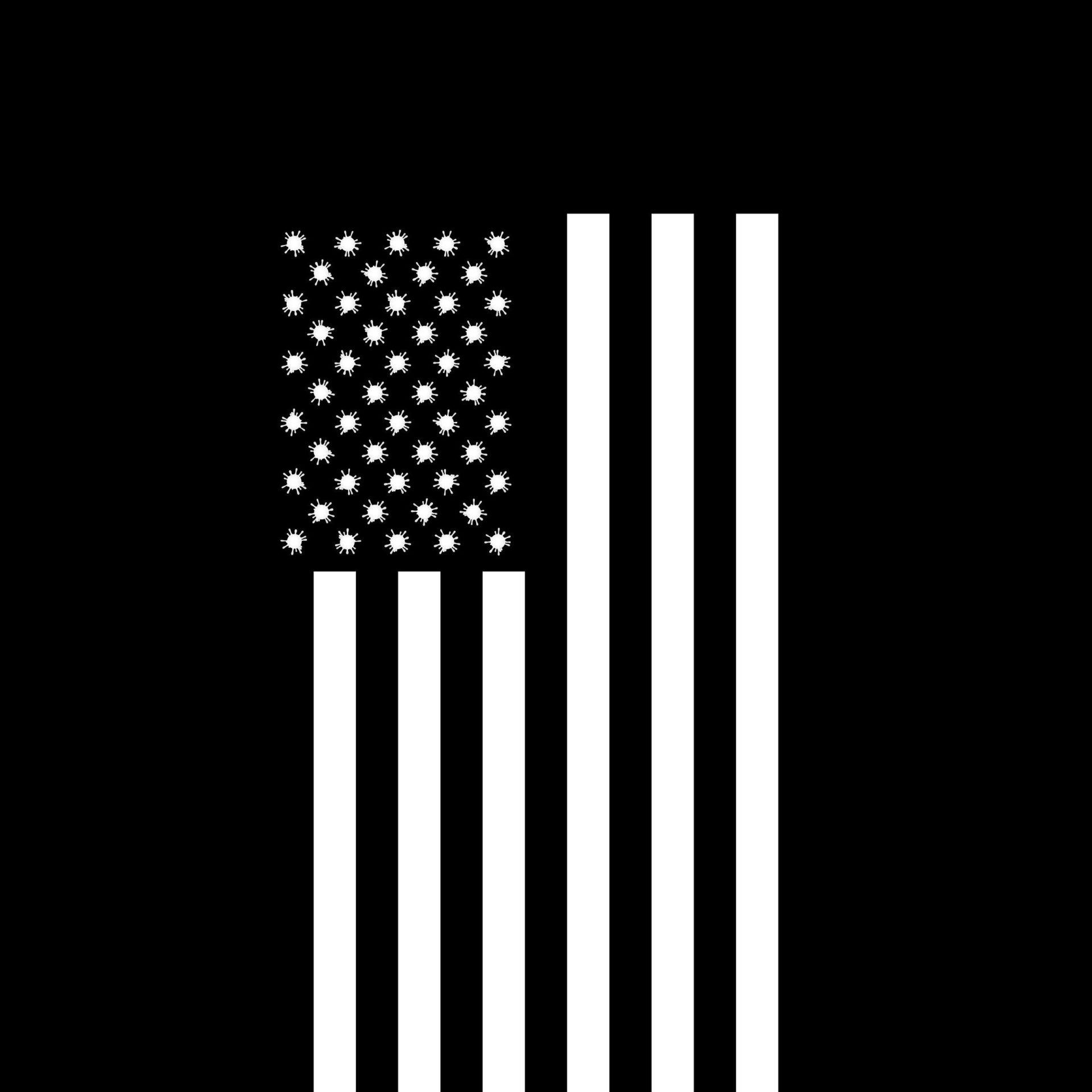

Graphic by Charles Deluvio | Unsplash

An Editor’s Note

As early as Friday, December 11th, the FDA could grant Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine. Other vaccines will most likely be approved as well, starting the long, arduous process of vaccinating our nation. The most promising vaccines from Pfizer, Moderna, AstraZeneca, and others were developed within a year, shattering all previous records for vaccine development. This tremendous achievement was made possible due to an unheard level of scientific coordination, global cooperation, and government support.

Still, the speed that these vaccines were developed has caused some to take pause about their safety and efficacy. These are not people who engage in bogus conspiracy theories or are outright “anti-vax,” but those who have legitimate concerns about political interference or want more information about the science. Understandably, titles like “Operation Warp Speed” do not convey an air of dependability.

Over the past couple of weeks, I have received several submissions from listeners and our community members expressing skepticism about these impending vaccines. Honestly, I was torn about publishing them outright, fearing that these honest doubts could unintentionally fuel unwarranted distrust in the process. At the same time, I believe that it is my job as the editor of our “clearinghouse of independent thinking” not to censor sentiments I knew that many Americans shared.

With that in mind, I decided to publish these two pieces side-by-side. The first is written by James Craven, a former journalist, discussing why he a “vaccine-hesitant.” The second piece is from Dr. Mark Langer, a former Associate Professor of Medicine at the University of Alberta who currently works as a family physician, directly responding to Mr. Craven and providing information about the process. Published together, I hope they offer a compelling conversation about COVID-19 vaccination, which will almost certainly dominate our news in the coming months.

– James Meadows, Editor of SMERCONISH

Why I Am ‘Vaccine-Hesitant’

By James Craven

First, let me be clear that I am not anti-vaccine. I get an influenza vaccine every year. I have been vaccinated for tetanus, typhoid, rubella, Hepatitis A and B, diphtheria, pertussis, polio, smallpox, and zoster. I believe in the efficacy of vaccines and their use in preventing unwanted illness. In general, I believe that vaccines are safe. But as I write this article, I am not sure about the upcoming COVID-19 vaccines. As Dr. Mark Langer recently pointed out in a Critical Thinking Essay, I could be described as “vaccine-hesitant” when it comes to vaccines for Covid-19.

As the Covid-19 virus continues to spread at an alarming rate, there is an understandable rush to produce, test, and distribute a viable vaccine. Overall, that is a good thing – we should want to protect the public as quickly and safely as possible.

Unfortunately, the push to complete the vaccine can be influenced by Donald Trump, a world leader who has a penchant for mistruth, exaggeration, and outright lying. In early December, President Trump was upset at the speed that the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) would make the earliest vaccines available. It appeared that Trump would rather rush a vaccine for political purposes rather than allowing the medical community to formulate a safe vaccine. That the process of granting an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to allow distribution was already moving forward at an unprecedented rate. Still, the president wanted it to be faster.

And herein lies my trepidation.

Granted, I am just a regular citizen. I am not a science wonk or a political junkie who knows the inner mechanisms of what it takes to bring a vaccine to the public. I am just a regular citizen. Still, with all the noise and conflicting messaging surrounding the vaccines, I am worried that corners will be cut for the sake of speed.

The bigger problem, in my opinion, is not just the acceleration of the vaccine process but the use of newer technology, namely messenger RNA (mRNA), to fight Covid-19. It is essential to understand that unlike a standard vaccine, the mRNA vaccines do not use a part of the actual target organism but instead use mRNA technology to replicate a specific protein to target only a part of the Covid-19 organism, in this case, the “spike protein.” This new process takes advantage of the process that cells use to make proteins trigger an immune response and build immunity to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19.

In contrast, most ‘traditional’ vaccines use weakened or inactivated versions or components of the disease-causing pathogen to stimulate the body’s immune response to create antibodies. In effect, this allows the body to learn how to fight the disease by producing antibodies that will do the job when needed. It has proven to be an amazingly effective method for battling diseases. Smallpox, a deadly disease, has been virtually eradicated. Polio, which was well known in my neighborhood when I was growing up, is all but a memory today. Other vaccines for mumps and chicken pox came too late for me. I suffered through both.

In the United States, vaccine development is a process that includes exploratory phases, pre-clinical trials, new drug application, four phases of vaccine trials, and thorough vetting from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration. This process is one that most people accept, which allows vaccines to be safe and effective. While vaccines like those used for smallpox may carry the threat of moderate to severe reactions, most are relatively benign due to the extensive testing performed before a vaccine is made available.

But that is not the case with the Covid-19 vaccines. Pfizer and Moderna’s newly developed vaccines are mRNA-based vaccines, which are being rushed toward production through an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA).

First, it is essential to understand that no current vaccines are used in the United States using mRNA technology. According to the Centers for Disease Control, clinical trials using mRNA vaccines have been carried out for influenza, Zika, rabies, and cytomegalovirus (CMV). These early trials encountered the instability of free RNA in the body, unintended inflammatory outcomes, and modest immune responses. Until December 2020, no mRNA vaccine, drug, or technology platform had been approved for humans. Before 2020, mRNA was only considered a theoretical or experimental candidate for use in humans.

And yet, we can expect this vaccine to be passed on to perhaps hundreds of millions of people worldwide. I do not pretend to be a scientist, doctor, or researcher. However, even a layperson must ask questions given that testing has been shortened. I understand that the mRNA process replicates the protein used to essentially cloak the spike protein, the characteristic fringe of projections on their cell surface. The idea is that the cloaking will stop human cells’ penetration and render the virus unable to transmit its pathogen.

I cannot help but wonder how specific the mRNA replicant is in its targeting? Is there a possibility that it could cloak other proteins with a chemical makeup close to the spike protein? If possible, how many other such proteins are there in the human body?

With the long-term testing of the vaccines delayed, what might we see in six or nine months? Imagine, for the sake of debate, that an adverse reaction is isolated in July 2021. Millions of people might be affected. We do not know because we have not done the testing done on all other vaccines before introducing it to the public. Is the United States even doing comparison testing with antigen-based vaccines already in use by China and other countries, or is xenophobia blocking our view of another solution.

According to The World Health Organization: A vaccine must provide a highly favorable benefit-risk contour; with high efficacy, only mild or transient adverse effects, and no severe ailments. The vaccine must be suitable for all ages, especially pregnant and lactating women. It should provide a rapid onset of protection with a single dose and confer safety for at least up to one year of administration.

I ho

pe my layman’s view is foolish. I hope that being “vaccine-hesitant” is just the view of the uneducated. I hope that the vaccines are all they are described and allow millions to return to everyday lives. I know that I will likely not be eligible for vaccination until late 2021, which means I will get to wait and observe before taking it.

In the meantime, I know that I am not the only one with these doubts and questions. Even some medical professionals say they are skeptical. Michal Linial, a professor of biological chemistry at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, said she is in no hurry to use the new vaccine in an interview with The Jerusalem Post. “Classical vaccines were designed to take ten years to develop,” she said. “I won’t be taking it immediately – probably not for at least the coming year,” she told the Post. “We have to wait and see whether it works.” Another article in JPost found that two participants in the Pfizer trial had died after receiving the vaccine; however, one of the deceased individuals was immunocompromised. Still, these facts are cause for concerns for ordinary people like me.

A Doctor’s Response

By Dr. Mark Langer

There are some genuinely mind-boggling theories in circulation. There is a theory that Dr. Fauci owns the patents on vaccines, and it’s all a scheme for him and his buddies to get rich. Another alleges that Bill Gates is funding the implementation of Agenda 21: A New World Order where Satanist Globalists enslave the human race. Others say that the vaccines contain microchips so “they” can monitor you, or it’s a scheme to sterilize our women.

Fortunately, I’m not responding to one of those. Instead, I will try to address genuine rational concerns from someone who is justifiably unsettled by aspects of the COVID vaccines.

Twenty years ago, a renowned orthopedic surgeon in Canada modeled for me a useful mnemonic to use for discussing an intervention like vaccination. “Remember BRAD,” he said.

To this day, I still discuss vaccination through this acronym. It stands for Benefits, Risks, and Alternatives (the “D” in the acronym stands for Document – advice for physicians to make sure the conversation is written down somewhere). It’s still the best framework for presenting options that I have learned and an invaluable tool that I shared with hundreds of doctors in training.

Benefits:

Vaccines will undoubtedly work to suppress SARS-CoV-2 if appropriately utilized. If they prove as useful as they appear – and enough people accept them – the coronavirus will eventually be starved of susceptible hosts and fizzle out. If we can maintain that immunity, all mitigation restrictions (staying apart, limiting gatherings, limiting activities, wearing facemasks) can eventually be lifted without fear of widespread, sustained transmission – potentially by next fall.

It is important to note that this virus is not going away. Even under ideal efficacy and uptake conditions, this is not smallpox. This virus is now part of this planet’s ecology. For the foreseeable future, factors like waning immunity, pockets of susceptibility, and animal reservoirs ensure that this virus is endemic. There will be intermittent outbreaks and clusters – even with “perfect” vaccine use, but Public Health will be able to identify them and stamp them out as we do periodically with measles and mumps. From what we know so far, this virus is unlikely to demonstrate seasonality, as influenza exhibits – but this is still a new virus that is less than a year old, with some characteristics that suggest that it could. Additionally, we don’t fully understand immune responses to infection with the virus or the potential for escape – periodic boosters of perhaps adjusted vaccines may be required. Thus, even the benefits have caveats.

Risks:

First, there is an infinitesimally small chance that vaccines will fail to be as effective as the evidence suggests. Due to the sheer size and robustness of the trials, it is statistically certain that they will trigger a neutralizing antibody response. That being said, statistical certainty is not 100% irrefutable – something unpredictable could render the immune response ineffective. Additionally, the effects on specific populations – like children, pregnant women, immunosuppressed people – are still unknown in the long-term.

Efficacy may not be universal, but it probably will be.

The second risk concerns the idea of inadequate safety. This concern is the most rational one by far, in my view. The speed of the process of vaccine development gives rise to worries that corners were cut. No vaccine has ever been developed this quickly, after all. Perhaps regulators were lax in demanding safety and efficacy protocols. Maybe pharmaceutical companies rushed the process sensing profits and prestige. These are all distant possibilities worth considering, but there has been no indication these hypotheticals have occurred.

Regarding how quickly we got the vaccines, it’s important to remember that we had dozens of mothballed vaccine programs after SARS (2003) – shelved when that virus naturally burned itself out. We got a huge head start by using the research from these programs.

Second, this virus’s shocking prevalence – more than 68 Million cases worldwide – paradoxically helped by speeding the trial process. It meant that it didn’t take long to reach the number of events required to measure efficacy. Additionally, the investment for research, development, and trials worldwide was enormous. Phase III trials, for example, enrolled some 30 thousand participants (previous efforts usually consisted of, at most, 3,000). Governments also underwrote vaccine production – with hundreds of millions of doses produced in anticipation of approval (i.e., they didn’t have to wait). It was quite the gamble for vaccine manufacturers – if the stuff didn’t work, they would have thrown all of those doses away and swallowed the costs.

Additionally, as ‘Dr. Mazz’ discussed with Michael Smerconish on CNN, the government promised to buy a set number of vaccines, which meant that no time was spent on the marketing and business side of production. In short: the “white coats” in the lab were not rushed.

Altogether, Operation Warp Speed worked.

Mr. Craven voiced a concern that there could be government interference and pressure to hasten development inappropriately. The concerns are partly legitimate. In September, the Trump administration demanded the FDA justify its ‘tough standards’ for vaccine development – raising the specter that the executive branch could pressure the scientists.

That being said, I am very encouraged that health authorities are more and more vocally resistant, and pressure has lessened – particularly in the wake of the US federal elections. That being said, there has been no indication that politicians have interfered with the process.

The results of Phase III vaccine trials from both the AstraZeneca and Pfizer trials strongly suggest they are safe. Continued Safety monitoring is planned, and Phase IV safety trials will continue in parallel with the anticipated first rounds of vaccinations. If some safety signal arises during the process of deployment, vaccination programs can be halted or adjusted. For example, 24 hours after starting their vaccination program, the UK reported anaphylactoid reactions in two vaccine recipients who had a history of bad allergy-like reactions. I feel, believe it or not, better with that news. They have adjusted their guidelines to include a warning not to vaccinate people with a history of severe allergies (if you have trouble breathing after a bee sting, for example, you shouldn’t take the vaccine). Our safety approaches have been demonstrated to be dynamic (In fact, I can guarantee that guidelines for administration will change further as we gain experience – this will not be the last adjustment).

Despite the sheer size of the Phase III trials, there is a real, albeit small, risk of unanticipated adverse events that didn’t show up yet as well. We have minimal real-world experience with the mRNA platform, in particular – as Mr. Craven noted. Risks are very low, but naturally-occuring reverse ‘transcriptases’ and ‘ribosomal vagaries’ could give rise to unanticipated problems. The hubris of humanity – “It will be fine. We know all there is to know about genetic function” – is jaw-dropping to me. The mRNA mechanism is almost certainly safe but makes me personally nervous. I share some of his trepidation.

The last risk to consider is more ethereal. I have friends and colleagues that voice a feeling of uneasiness. They describe concerns that “something else is going on here.” Though not based on any evidence, they express concerns that autonomy is being assaulted, rights infringed, and freedoms limited.

I don’t lend them much weight, but they certainly qualify as “risks” for many. They have an appropriate place in personal choices.

Alternatives:

First, we could do nothing and allow the virus to do what it will. A recent study from Manaus, Brazil, found that the infection rate did slow naturally without intervention, but not until 76% of the population was infected. Extrapolated to the US population would be equivalent to 250 Million infections and, conservatively, 1.25 million deaths. Far more importantly, in my opinion, health systems could not manage 12.5 Million additional patients in hospitals – even were that tidal wave staggered. Projections based on data like these are why public health authorities are urging political leaders (e.g., Governors, Premiers, and Presidents) to act. According to almost all healthcare infrastructure experts, we cannot manage a laissez-faire strategy based on accumulated data and modeling.

“Vertical Interdiction” is another option in active discussion. The idea is to shield the highest risk people (elderly and those with comorbidities) while letting the virus spread in the low-risk. Criticism of the plan is widespread, but it is an alternative being advanced of which people should be aware of.

As a third alternative to vaccination, severe lockdowns with a “COVID Zero” mindset could be attempted – lockdown tightly until the virus is starved out of existence. Australia enacted this strategy over the summer with mixed results (costs are still being measured, though residents are satisfied), and it should be noted Australia is still hypervigilant – their pandemic is not “over.”

A fourth alternative is to keep doing what we have been doing – mandating mitigation measures like face mask use and social distancing – and imposing restrictions indefinitely or cyclically. Businesses could apply the principles of hygiene, distancing, masking, and airflow more stringently. It’s a poor option and doomed to failure in my opinion (asking for more from businesses is a mistake), but it’s an option.

Lastly, besides vaccines, there are other innovative interventions in development that we could wait for. Some advocate for home testing, which is more and more feasible with the technological advances that make home antigen tests easy-to-use and accurate. I am personally hopeful that ultra-rapid testing will allow us to have cheap, nearly instant point-of-access testing at some point in the future. I envision COVID-Breathalyzers that we blow before accessing businesses, theatres, or arenas. Trials of these new tests are already being done.

My bottom-line message to any “vaccine-hesitants” is that the apprehension is valid. There are personal Risk-Benefit calculations to be made. I might feel differently about supporting autonomous decisions if we were struck with a plague of biblical proportions, but we got SARS-CoV-2 as our overdue pandemic pathogen. There is urgency, but also latitude.

If citizens are aware of the potential benefits vaccines provide, don’t hold QAnon-level delusional beliefs about risks, and are aware of the alternatives, my old professor would be happy.